“You’d be more comfortable if you relax with yourself. We don’t invent our natures, they’re issued to us, along with our lungs…and everything else. Why fight it?”

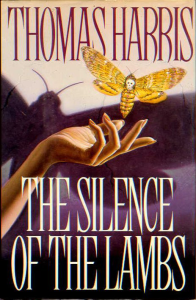

In the two best adaptation of William Harris’ series of Hannibal Lecter novels, the films delineate two distinct portraits of the psychological profile contained within not just the serial killers, but more interestingly, also within the investigators responsible for apprehending them. Throughout Michael Mann’s 1986 seminal crime procedural adaptation of the Red Dragon novel and Jonathan Demme’s 1990 masterpiece adaptation of the book’s sequel—The Silence of the Lambs—the complex moral challenges facing both manhunters allows a fascinating glimpse into issues of gender and psychological insights contained within both FBI Special Investigator William Graham (William Petersen) and the young FBI trainee Claire Starling (Jodie Foster). Specifically, this contrast is viewed through the mutual interaction between both investigators and Hannibal Lecter–the cannibalistic serial killer aiding both manhunters in the pursuit of the killers beyond their reach.

While Silence revels much more in the serial killer genre elements with procedural clues in the background, Manhunter brings the police procedural ideas to the forefront. Manhunter’s basic thesis revolves around the thin line separating the psyche between serial killers and the obsessive nature of those investigators attempting to “solve” them. Over and over, Mann highlights the dual identity that Graham must negotiate between being a “good cop”, who uses the obsessive nature of his persona to stop criminals, and how that same obsessive nature taps into the dark reservoirs of his psyche that overlaps with the same perverted landscape as the killers of his pursuit.

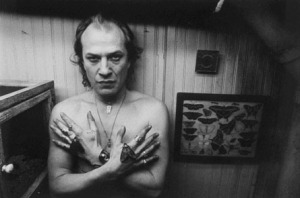

In Graham’s introductory scene, he’s persuaded by his FBI Superior Jack Crawford to return to his job as a special investigator after being committed to a mental ward for his arrest of Hannibal Lector. In his first real scene of police work, Graham effectively places himself in the mind of the current killer—codenamed The Tooth Fairy —and recreates his actions within the scene of the murder. Graham effectively uses a method actor’s technique of embedding his thoughts into the mind of the killer in order to piece together the crime from the murderer’s perspective. He talks out loud to himself, plays the role of the Tooth Fairy, speaking into his recorder: “God she’s lovely isn’t she…you opened their eyes, didn’t you! Didn’t you!”

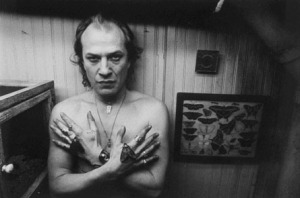

Later, Graham meets with Lecktor (only ever unnecessarily spelt this way in Manhunter) for further help unlocking the identity of the killer. Played by Cox in a much more naturalistic and intellectually driven behavior than that of Hopkins, Lecktor taunts Graham’s plea for help, knowing that Graham’s arresting him continues to haunt him beyond the thin veneer of his outward confidence. Lecktor even (sloppily) underlines the film’s thesis by telling Graham in a bald declaration: “the reason you caught me is we’re just alike.”

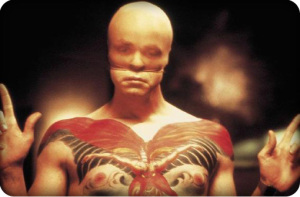

The idea of transformation—or becoming—is another theme echoed throughout both Manhunter and Silence. In an uncovered note from Francis to Lecktor, he writes: “You alone can understand what I am becoming. You know the people I use to help me in…undergoing change to fuel the radiance of what I am becoming.” As Francis Dolarhyde (aka the Tooth Fairy) kills his victims in the act of becoming the Red Dragon, Graham struggles against becoming locked in the very acts that he’s committed to fighting. LIkewise, Lecktor’s final piece of advice to Graham in unlocking the killer’s motive involves “becoming”:

“Didn’t you really feel so bad because killing him felt so good and why shouldn’t it feel good? It must feel good to God. He does it all the time.”

“Why does it feel good, Dr. Lector”

“…because God has powers. And if one does what God does enough times, one will become as God is”.

Mann further implements this motif by framing Graham’s investigative obsessions in a manner that suggests his own becoming not altogether unlike Dolarhyde. The pre-credit opening is shot from the POV of The Tooth Fairy ascending the household steps to murder the family, and when Graham breaks into the house for his own investigations, Mann replicates the same POV shot to parallel the perspective of the two men. Similarly, this transitions into Graham’s own unlocking of the killer’s psyche—allowing his realization that the Tooth Fairy needs to use mirrors as an “audience” of his becoming. Furthermore, Graham must continue to watch the home videos of the family in the same ritualistic manner as the Tooth Fairy. In watching the videos over and over again, Mann again demonstrates how Graham’s practices for success border that thin line between investigator and the killer.

As Graham falls deeper and deeper into the case, Graham’s son forces him to confront this very nature that he’s demonstrated an inability to control, asking:

“This guy’s trying to kill us?…When are you gonna kill him?

Mann ingeniously uses the innocent of the child’s question in order to again highlight the thin moral boundary separating the two men. A guilty look flashes across Graham’s face: his own son’s question reflecting an idea not too different from the same taunts used by Leckter. Similarly, the question—and his son’s point-of-view of right and wrong—display a failing on Graham’s part to truly define exactly what the moral justice side of his job means. Almost reluctantly, he answers:

“I’m not…It’s only my job to find him.”

However, this does not prove to be the case.

As with Lecktor’s insight that a killer kills because it feels good—to act like God—and if one kills enough times than one will become as God is—Graham cannot stop himself from needing to act like these killers in order to become one. After spending the entire movie using the same obsessive mindset utilized by the killers in order to fulfill their conquests, Graham finally finds the killer of his pursuit and shoots down The Tooth Fairy. Although Mann employs the cinematic style of an action/cop hero forced to kill the bad guy, and the film ends with Graham back on the beach with his family, the question remains whether Graham’s process hasn’t exactly validated Lector’s claims. Though innocent lives have been saved, Graham has now—multiple times, and in the same, serial manner—killed two men by enslaving himself to the same psychological compulsions that compelled the very men that he’s just killed.

Though Lecktor believes that it is in replicating God’s power to kill that drives the Tooth Fairy, Graham can now be seen as one occupying another spectrum in the desire act as God—specifically, in acting as the all-powerful protector. Just before Graham leaves to take on the case, he works with his son to help a build a fence to keep out predators—protecting the innocent animals. Throughout the investigation, Graham continually consults the photos of the murdered families (along with their home videos) as a continual reminder of his responsibility. Nearing the climax, Graham finally yells at Crawford for roping him into the case by shouting:

“You showed me two dead families knowing damn well I’d imagine families four, five, and six”. To which Crawford retorts: “Damn right. And I’d do it again”.

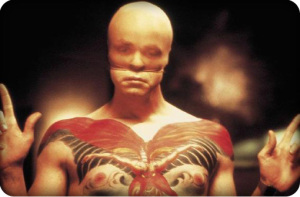

The idea of Graham as protector and father is further underscored by challenges of masculinity repeatedly addressed in the film. In the investigator’s need to outsmart both Lecktor and The Tooth Fairy as a way of proving masculine dominance to himself, family, and co-workers, Mann again uses a parallel structure between The Tooth Fairy and Graham to negotiate their dual struggle. The police’s main assumption about the Tooth Fairy—that he is gay—is proven to be something that troubles and provokes Dolarhyde into fits of rage. After kidnapping Lounds (the paparazzo), he asks point-blank: “Do you imply that I am queer?” Though Lounds profusely denies it, Dolarhyde forces him to “promise”, which he concludes by stating “We’ll seal your promise with a kiss” (before then sending Lounds to his death).

Though some may point to Dolarhyde’s night of “romance” with his blind co-worker, Reba, as an argument against any homosexual inclinations, what one finds on close examination is that she is further framed as yet another prop in Dolarhyde’s slow transformation toward becoming the Red Dragon. After their night in bed, Dolarhyde wakes in a panic upon finding her absent. He races outside looking for her, only to find Reba standing in the rising morning sun. When she talks about coming back inside the house, Dolarhyde begs her stay outside because: “you look so good in the sun”.

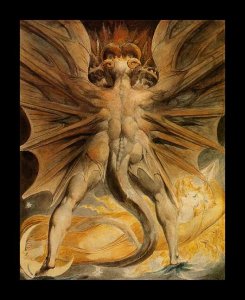

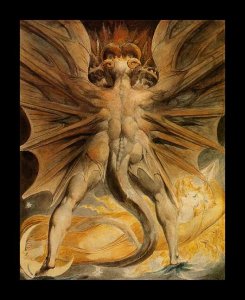

This is a clear allusion to main source and inspiration of Dolarhyde’s Red Dragon ideal through the William Blake painting: The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in the Sun. With Francis standing in for the Red Dragon, Reba is literally standing outside in the sun, fueling his fantasy in acting as the woman literally clothed in the sun.

In line with Graham’s role as father figure and protector, he, too, feels the need to prove his masculinity through the job. Beside the photos/videos of Graham watching as a father might, desperate to protect his family, he’s quick to anger and easily provoked by any threat to his shortcomings. With Lecktor–Graham’s ultimate tool in unlocking the clues to the killer–he’s unable to ever let pass any provocations by the jailed cannibal. During his first visit to ask Lecktor’s help, when Lecktor asks why he would ever aid the police in finding the Tooth Fairy:

“Thought you might be curious to see if you’re smarter than the person I’m looking for”

“By implication, you [Will], are smarter than me”

“You had disadvantages…You’re insane”

“Don’t think you can persuade me with appeals to my intellectual vanity”

“I’m not going to persuade you. You’ll either do it or you won’t.”

Graham deflects Lecktor’s assertion of Will being smarter than either of them by resorting to Lecktor’s insanity, and when Lecktor continues to taunt their similar natures, Graham flees the asylum from being so overwhelmed by the implications. In contrast to the finesse and verbal outsmarting used by Clarice in Silence, Graham’s response to any version of insulting his “less than” is to prove himself the better. Later, when Graham explains to the investigators (with Lounds in attendance) that the Tooth Fairy may be impotent with females, Lounds asks how working on the case affects Graham’s own sex life. To which he responds:

“Mine? Doesn’t affect mine. Affects yours. Go fuck yourself”.

Again, unlike Clarice’s reactions in Silence to utilize any abject response to her sexuality as a means of subverting expectations to her advantage, Graham—as a man compelled to prove his masculinity—ends up sharing psychological qualities not altogether unlike those of the Tooth Fairy.

Graham’s obsession as both a protector and father figure, and then decision to kill in the name of it, further supports Lecktor’s explanation to not just The Tooth’s Fairy psychology—but Graham’s. Again, although the film ends on an ostensible sunset of triumph for Graham, there remains a darker reading into Graham’s “feeling good” for having fully completed his cycle of becoming more like God the protector.

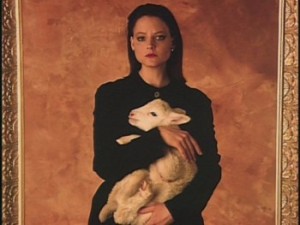

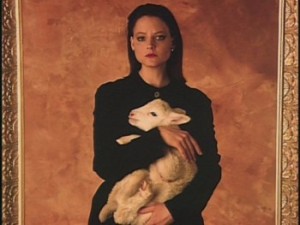

Clarice Starling, although an FBI novitiate in training to fulfill the same position occupied by Graham, works as a fascinating counterexample to the troubled male investigator. While Graham’s pathology has proven to be linked to those of the very killers he seeks, and further complemented by his masculine mindset, Clarice works both on the opposite side of the spectrum and strategically utilizes her disadvantages into her advantage.

Clarice is introduced as an FBI trainee, one not even officially introduced into the field, and furthermore—as a woman. Without exaggeration, almost every scene involving Clarice is framed from either her literal point-of-view or displays how men in the field treat a woman, much less a trainee. The first shot of Clarice is training at the FBI training headquarters—climbing a hill—overcoming man-made obstacles. Not a moment later, this is followed with her entering a crowded elevator filled with men drawing her height, where she must force her way inside only to confront their glaring stares. She then meets with Crawford (played, as great as Farina’s moustache will always be, perfectly by Scott Glenn). Here, Crawford offers her the goal of talking with the notorious Hannibal “The Cannibal” Lecter under the pretenses of interviewing him for an FBI psychological profile. Clarice eyes the Buffalo Bill headlines posted behind him, playing along, as Crawford adds: “I don’t expect him to talk with you, but I have to at least say that we tried.”

At Lecter’s insane asylum, Clarice enters a whole new realm of misogyny from both the staff and those interred at the criminally insane. Chilton—the director of the Baltimore asylum holding Lecter—charms Clarice with such lines as:

“We get a lot of detectives here, but I must say, I can’t ever remember one this attractive.” … “Will you be in town overnight”…”, “Crawford’s very clever using you, isn’t he?…Pretty, young woman to turn him on. I don’t think Lecter’s even seen a woman in eight years, and oh are you ever his taste”.

After deflecting Chilton’s first few words, Clarice snaps on the last: “I graduated from UVA, Doctor. It is not a charm school.” When she then suggests that she be left alone to interview Lecter, and Chilton passive-aggressively notes that she could have mentioned that earlier, she replies: “Then I would have missed the pleasure of your company”.

Unlike Graham’s volatile attitude toward even the smallest chide, Clarice must navigate the male-dominated criminology field with a level of self-aware tact. While Graham’s only real obstacle came from within himself and those criminals of his pursuit, Clarice must contend with both sadistic killers and the constant, looming male bureaucracy challenging her competency at every turn.

.

.

In Clarice’s first interview with the imprisoned cannibal, Hannibal is insulted both by Crawford’s sending of a trainee and Clarice’s not so subtle questionings that are the equivalent of filling out a standard psych eval. On her way out, however, one of the deranged inmates—Migs—degrades Clarice in one of the vilest methods imaginable: by literally throws semen on her face. An infuriated Lector, who considers Migs’ discourtesy to be “unspeakably ugly”, immediately calls Clarice back and gives her the first clue in catching Buffalo Bill—who is connected to Lecter through a former patient during his days as a psychiatrist.

One wonders if this incident had happened with Graham or another male investigator, rather than Clarice, how the pursuit of Buffalo Bill would have continued forward. Migs would be understandably less inclined to humiliate a female investigator, and Lecter himself seems more repulsed by the discourtesy to a female investigator than those male investigators routinely sent to interview him. Despite Lecter humiliating Clarice only moments before, calling her: “a well-scrubbed rube. You’re not one generation removed from poor white trash.” Migs’ disrespecting a woman in this particular way revolts Lector to the core so much so that he allows Clarice for the first of many breakthrough in finding Buffalo Bill.

As strong as Clarice remains following the incident, she breaks down when reaching her car in the parking lot outside the institution. Alone, without anyone watching, she lets out a long cry that leads to a flashback from her youth. Here, Clarice’s motivation and inspiration for her career is first revealed as her father—the local sheriff—returns home from work. The role of this man in Clarice’s life proves to be the source of her strength, and the defining model of what a strong and decent man can be in contrast to the more despicable men that will populate the remainder of her working years.

When investigating the first clue, Clarice again demonstrates her resourcefulness where many men would turn back or ask for help. Following Lecter’s lead to a storage unit, Clarice and the storage manager are unable to open the long-jammed door. While the manager suggests that his son could help, Clarice finds a tire lift in the back of her car and manages to lift the door enough to crawl inside the long abandoned facility, while the manager stares dumbfounded at her ingenuity.

Still, much of Clarice’s noteworthiness lies in her silent resilience, an ability to trudge forward in perseverance despite the setbacks or constant humiliation from either her peers or the killers. In her second interview with Lecter, he asks: “Do you think Jack Crawford wants you sexually? True, he is older, but do you think he visualizes exchanges, scenarios—fucking you.”

Whereas Graham, in his endless need to prove his position of alpha superiority, would no doubt be ready with some hotheaded comeback, Clarice returns with a simple shake of the head and replies: “That doesn’t interest me, doctor. Frankly, it’s the sort of thing that Miggs would say.” Again, using her intellect and subtle passiveness to turn the tables on Lecter, and in effect, beat him at his own game of mental intimidation.

When Buffalo Bill’s next victim is found, Clarice and Crawford travel to the funeral parlor to inspect the latest corpse. But first, Demme uses the opportunity to again expose Clarice position in the workforce. Demme places the camera from Clarice’s POV, and the eyes of every officer in the room stare down upon the woman as she pushes through the crowded funeral home to the backroom parlor. When Crawford speaks with the Sheriff, and the latter begins discussing Buffalo Bill’s mutilations to the woman’s corpse, Crawford utters loud enough for the room to hear: “Sheriff, this type of sex crime has certain aspects, I’d just as soon discuss in private…you know what I mean” before letting his eyes visibly direct toward Clarice.

Despite her clear competency to both draw out information from Lecter in a manner so many of her male peers have already failed, Clarice’s male FBI superior belittles her before the entire male squad. When Clarice does gain entry to the parlor room, and finds the death moth secreted within the corpse’s throat, she again demonstrates her impressive analytic prowess. In the car ride afterwards, Crawford comments to Clarice: “When I told that Sheriff we shouldn’t talk in front of a woman, that really burned ya, didn’t it? It was just smoke, Starling. I had to get rid of them. She replies: “It matters, Mr. Crawford. Cops look at you to see how to act. It matters.”

Later, with an attitude not too dissimilar from Graham’s in dealing with Lounds’ taunts, Chilton tries outsmarting Lecter in the most obvious, masculine way possible—bullying him. In his hopes to humiliate Lecter, and his exploiting the opportunity as a means of demonstrating his power, Chilton destroys Clarice’s more clever and subdued path toward finding Buffalo Bill. (In the end, Chilton’s plan proves even more destructive when Lecter’s able to escape from imprisonment.) But yet again, the series has proven that this masculine response of aggression—mirroring the killers’ own compulsions to fuel their dangerous fantasies—leads to disastrous results.

In their last interaction together, Lecter agrees to continue his arrangement with Clarice of helping profile Buffalo Bill under the condition that she reveal her most painful memory. Clarice speaks through a choked up voice, recounting the incident after she ran away to a farm in Montana after her father’s death. There, late one night, she heard the screams of the lambs being slaughtered. Hoping to silence the horrible sound, she sneaks in, steals one of the lambs, and ran as fast as she could—thinking that if she could save just one…

Besides explaining the title, Clarice’s story sheds light on her psychology and driving motivation in a manner both illuminating and heartbreaking. When Lecter asks if she ran from the sight of the slaughtered lambs, Clarice politely refutes him—making him understand that she opened their pens, but they wouldn’t move, the lambs were confused and wouldn’t run…but she was compelled to help save them. With the obvious metaphor for the sheep as the helpless victim, Clarice has been driven all her life to not look away from the danger, to be strong as she saw her father, and use her smarts to help those confused and dumbfounded by the situation in order to save the helpless victims.

Rather than wanting to punish those responsible for the violence, Clarice’s drive has always been focused on saving the victim. While Manhunter’s title is changed from its novel adaptation of Harrris’ Red Dragon, it still encapsulates so much of what defines Graham as an investigator compared to Clarice. Whereas the former relies on his inhabiting the mindset of the killer to the point that he himself arguably transforms into one, Clarice remains unaffected by any such dangerous pathology by knowing that her job relies in her helping to save the innocent. While she is indeed the one to kill Buffalo Bill by the film’s conclusion, her shooting him in self-defense plays out with a world of difference compared to Graham’s. Clarice’s inability to answer Lecter’s final question as to whether the lambs have stopped screaming only helps prove this point further. While Graham views himself as the man responsible for stopping the slaughterer, Clarice operates under the hope that she may always be in service of helping save just one more.

While both investigators are working toward a similar, admirable goal, the stark differences in psychology and methods between Will Graham and Clarice Starling highlights the vast difference between the two and respective consequences of both. Graham’s method of embedding himself within the same, sadistic moral point-of-view as the killers has been proven to be successful in stopping the slaughters, yet still morally questionable in terms of its endgame. In his pursuit of justice, Graham himself begins to transform into the same type of monster that he’s promised to stop—ending in his compromised morals and continued psychological suffering.

Clarice, on the other hand, is driven by the traumatizing effect of violence in hoping to save the victim, rather her needing to solve what is an impossible goal—of defeating violence with violence. Instead, she uses her own unique gifts—skills and training crafted through a lifetime of education and experience to help stop the suffering of those in need. And perhaps most fascinating, the psychology of both investigators is discovered through their relationship with Lecter—the link in finding the killer of their respective pursuits. Where Graham and Lecter continue an endless push-pull of trying to outsmart one another, Clarice uses Lecter’s own psychological tactics to her advantage without needing to compromise herself. In the end, both films demonstrate why the investigators and Hannibal Lecter remain such superb examples of how Harris’ morally ambiguous novels continue to intrigue audiences and expose the wide spectrum of human nature for all its good and evil.