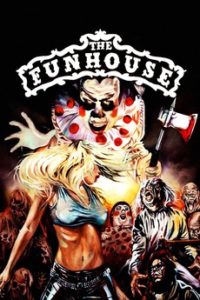

Part of Criterion’s 80s horror collection. * Spoilers *

After creating the most nightmarish house of horror of all time in Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Hooper turned his attention toward a slasher set within a literal funhouse of horror in THE FUNHOUSE. While this actually works as an interesting transitory piece within his haunted house trilogy of sorts between Chainsaw and Poltergeist, Funhouse is undoubtedly the weakest entry of the three and unfortunately never lives up to potential of its premise – though certain horror elements in the last third deserve special consideration.

Furthermore, the aspects that successfully standout – the monster himself, the production design of the carnival, the generally sleazy / southern white trash aesthetic for which Hooper had a particular penchant are all incredible – but unfortunately do not come together in a unified way until the last third.

Instead, the first two-thirds are unfocused, unevenly paced, and filled with way too many competing subplots. Like Chainsaw, Hooper spends considerable time with the inevitable teenage victims for most of the first half – watching them on a normal Friday night at the carnival, hinting at horrors to come, the dynamics between them, and restraining himself from unnecessary jump scares or too much foreshadowing – allowing the audience to wallow in just hanging out with the teenagers as though part of the group.

Unlike Chainsaw, which was shot on grainy 16mm to create a documentary feeling that added another unnerving layer, The Funhouse quartet are forgettable and fairly dull. Additionally, there is a subplot with the lead – Amy (Elizabeth Berridge) – and her younger brother too which far too much screentime is dedicated with almost no payoff. The film starts off with this younger brother in an homage to both Halloween and Psycho (and as a set-up for a larger role in the ending) but this ends up mostly serving as a continual red herring.

Moreover, the first two-thirds are filled with diversions into the world of the carnival that lead to the film’s uneven pacing instead of creating an atmospheric sense of horror. While Hooper seems to be having fun indulging in all the hallmarks of the local carnival – the fortune teller, the magician, the freaks-of-nature exhibit – the characters are only given a cursory scene or two instead of being more involved as a ‘family’.

The barker and leader of the carnival hints toward all these sideshow performers being a ‘family’, which would have been more interesting and created a Sawyer-like dynamic with the monster being the Leatherface that the rest of the carnies looks after, but this dynamic never really comes to fruition. Lastly, there is a cliché religious fanatic screaming about God’s judgment that, yet again, is unfocused from the main premise with little payoff and could have been cut with little consequence.

All these criticisms are only directed toward the fact that the last third of the movie finally comes to life in a focused, fun, and atmospherically terrifying way which unfortunately feels rushed due to the messy first two-thirds described above.

The monster – aka the son of the Barker – certainly has shades of Leatherface as a deformed killer and mistreated son. However, this movie lacks a scene like the ‘dinner table’ scene in Chainsaw or the ‘one of us’ scene in Todd Browning’s Freaks: a scene in which the audience’s POV character enters the nightmarish underworld of the sideshow assemblage to witness their camaraderie and familial bonding due to a lifetime of rejection from the normal world.

Hooper certainly has fun with the carnival production design – making use of puppets, leering clowns, haunted house flickering lights, and a laughing animatronic fat lady at the end – but even these are lacking compared to something like the subterranean world that the Sawyer clan has refashioned out of the abandoned carnival found in Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. Perhaps Hooper had this in mind (or a larger budget) when making that Chainsaw sequel a few years later – for the scope and nightmarish proportions of an underground world inhabited by the Sawyer family to which the ‘above ground’ world remains oblivious has a much more haunting effect when Stretch finally escapes at the end of that incredible horror sequel.

Nonetheless, the final sequence between Amy and the Monster in this movie – in which the latter chases Funhouse’s final girl until ultimately being crushed between the carnival ride gears while flashing lights blink on-and-off to lend stylish atmosphere to the climax – works as the most horrifying sequence in the film. A sequence about twenty minutes long which ultimately reminds the audience how much more effective this would be if stretched even longer and not hampered by the uneven pacing and overstuffed plotting of the first half.

Funhouse is a mixed-bag: filled with a great monster/slasher, set-pieces, and atmospheric potential that never fulfill their full horror possibilities but are still memorable in considering them almost as a first draft of sorts to what the master horror director, Tobe Hooper, would achieve just a few years later within two of best horror films of the 80s – Poltergeist and Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 – much more successfully.