In a crowded landscape of action movies attempting to dazzle audiences through an abundance of special effects and increasing scope of story, George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road manages to subvert both tropes in the service of the two most important aspects of storytelling that make the action matter: characters and theme. Though the fourth film in the series still offers jaw-dropping spectacles and astonishing set-pieces that allow for its ranking as the current benchmark for pure action filmmaking, one can easily miss how remarkably well this story also manages to weave ideas of character and theme (through mostly visual means) in order to raise the emotional stakes that allow for these action sequences to obtain their remarkable power.

Much to the frustration of more literal-minded audiences that desperately cling for continuity, Miller has again opted to basically uphold only the titular character of the franchise and his strange setting somewhere in a post-apocalyptic future. The first film—Mad Max—works effectively to present Max’s transformation as a figure of authority in the MFP to his new identity as a lone gun working outside traditional society. Mad Max is a great, mean film—one that helped launch the career of both Miller and Mel Gibson, while also helping to explode the Ozploitation movement on a national level. Nonetheless, the film also misses the true sense of minimalist storytelling, streamlined action, and unprecedented set pieces that would ultimately define the franchise to come.

Yes, admittedly, this is still low budget filmmaking at its best. Miller works wonders with a budget in the thousands to produce a movie that launched his career and innovative car chases that are still imitated by lesser films to this day. Moreover, the first Mad Max imbues a sense of raw, mean, rough-around-the-edges quality that is part of its lasting charm. The scene of Toecutter taunting Max’s wife for her “pretty face”—threatening to kill her and her baby while Max is out of sight—is brutal. Miller applies a sense of atmosphere, palpable tension, and escalating sense of uneasiness to magnificent effect. Afterward, with his wife and family taken from him, Max Rockatansky transforms into Mad Max—donning his iconic costume and hunting down the violent gang until the creative, final conclusion that would be reused to launch the Saw franchise decades later.

Nonetheless, like all great sequels, Miller uses his follow-up film to expand and intensify those pieces of story established in the original entry in order to indulge his sensibilities to their most ambitious effect. The Road Warrior—titled so for those unaware of the first Mad Max (and thereby indicative of the very loose connective tissue between the films)—elevates the unique mythology of Miller’s imagination to its fullest extent. Max now resembles something closer to the Leone western hero. A mythic, more archetypal figure of the lone wanderer that wiggles his way into moral conflicts of good and evil between the underdog and the domineering faction which he will help defeat.

Most importantly, The Road Warrior presents those hallmarks of Miller’s creative inclinations that would define the franchise as a whole: inventive, visual character designs, a streamlined plot, and set pieces that would raise the bar for action filmmaking across the spectrum. Specifically, in terms of the latter, the semi-truck chase between Max, the villagers, and Humungus’ gang, stands as one of the best chase sequences in film history. Often-cited as inspiration for those chase sequences that would later attempt to rival it—Speed, Terminator 2, Matrix Reloaded—no film has still yet been able to cater to those assortment of inventive and extraordinary inclusions that make that chase so unique: the gyro-copter, the bizarre vehicles, the outrageous character designs, the multitude of weapons that Max must defend against while attempting to steer the truck to safety. Additionally, the film displays the pulse-pounding editing and furious sense of pacing—coupled with a clear sense of action geography—that would ascend this chase toward its ranking as the peak of action filmmaking for its time.

Lastly, though a film marred by bizarre storytelling choices in craft its second half, the first half of Max Mad: Beyond Thunderdome presents further evidence for cementing the franchise’s legacy as the most inventive in its class. Though co-directed by George Ogilivie due to Miller’s difficulty in following through with the production in the wake of his producing partner’s death (Byron Kennedy), Beyond Thunderdome contains creative choices that simply don’t work in the latter half. The sound effects in particular, during the children’s takeover of the underworld, are almost comically out-of-place for a franchise whose strongest connective tissue can be found in its tone. Despite the memorable, idiosyncratic, and bizarrely lovable qualities of the feral child in Road Warrior, the entire inclusion of the tribal children in Thunderdome feels out of place. Tonally, they resemble something closer to The Goonies (released only a month earlier), the Lost Boys, or a watered-down Lord of the Flies. While this is not a criticism in of itself, it’s the fact that they are so conventionally identifiable from a visual standpoint that marks them as so out of place from a franchise where almost every other imaginable trope has been so utterly reinvented and distinctly tailored for this series.

Still, the first-half—and in particular, the Thunderdome sequence of the title—are Miller and the world of Mad Max at their best. Bartertown feels like an expansion of Humungus’ gang into an entire population of bizarre characters each with their own unique histories and identifies instantly recognizably from their visual design—none more so than the infamous Master and Blaster. Though Tina Turner’s Aunty is undeniably the weakest villain entry the series, she does lend a further sense of eccentric distinction that must be commended.

Max’s fight with Blaster within the gladiatorial Thunderdome itself—a wirework gladiatorial arena where the warriors fight one another while suspended by bungee chords and must seize whatever weapons are proffered by the spectators—stands as one of the most influential and gloriously inventive action set pieces ever conceived. One that has been imitated countless times since. Between Miller’s instant subverting of expectations when Max is able to find Blaster’s weakness, or the embracing of every conceivable creative weapon (chainsaws, swords, spikes), the Thunderdome set piece remains an ingenious playground for Miller’s imagination to filter his action fetishes in the apparently conclusion of Mad Max Trilogy. Though thankfully, this was not to be the case. As thirty years, Fury Road finally returned Miller to the fourth entry in his Mad Max series.

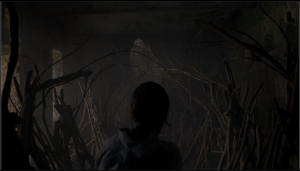

The Max of Fury Road is a mad animal. With sparse news reports and vague voice-overs for those unfamiliar to the series, he is now a shaggy-haired beast of a human being—feeding himself from (two-headed) rodents and only living to survive. He is immediately captured, his vehicle stolen from him, and destined for life as a blood-bag for the Warboys—servants of Immortan Joe, the leader of the Citadel. However, on this particular day, Imperator Furiosa—tasked with driving a War Rig to retrieve gasoline—has stolen his five wives and intends to deliver them safely to the mysterious Green Place.

Despite the change from Gibson to Hardy, and a higher budget that truly allows for Miller’s imagination to flourish, Miller wisely ensures that the narrative never inflates disproportionately to the simple story at the center of the chase. Similar to how Bartertown felt like Humungus’ gang expanded into a city, Fury Road feels like the chase sequence of Road Warrior expanded into an entire narrative. Most interesting, and different for the series, is that this film is domineered more by Furiosa than by Max. While Max is again the lone warrior now tangled up in helping the others, he also comes to learn the value of companionship in a manner very much in line, though still starkly different, than what has previously been seen of his character throughout the series.

As a blood-bag, the idea of Max as a primal, animalistic being is emphasized more than ever. He is literally muzzled like a dog for most of the beginning, and the few sounds he initially makes when meeting Furiosa are mere grunts. When he first meets Furiosa and the wives, he needs their help in cutting off the chain upholding his muzzle, essentially cutting loose his leash. Still, even when Furiosa asks his name, Max maintains his animalistic nature by refusing to offer one, asking instead: “Does it even matter?”

But unlike the villagers of Road Warrior or the Tribal Children of Thunderdome, Furiosa and the wives are as important to Max’s survival and capable of carrying their own thematic weight as to elevate the action scenes more than ever before. When Immortan Joe and his followers first see that Furiosa has veered from the course, and the warlord moves to investigate, the audience quickly understands their horrifying prison—and glimpses of their backstory—in a matter of seconds. “We are Not Things” is scrawled within their sanctum, along with “Who Killed The World”, brief but powerful visual lines that sum up a backstory more than any long, expository monologue could ever entail.

Furthermore, and easy to miss because it is so quickly glimpsed: various green plants decorate the interior of the sanctum when Joe is rushing inside to find his five wives—a detail with important implications for the plot’s latter half. Later, freed from their prison, Furiosa cuts a vagina dentata-esque chain clearly used by Joe further enslave the wives. This idea of the women as property—beings incapable of serving their own agency—works tremendously well in the context of not only a Mad Mad movie, but a chase movie in particular, where the characters are literally driving to free themselves from the confines of a city of men that enslaved them.

As the major storyline revolves around this one major chase between Immortan Joe and Max/Furiosa/the five wives, Miller retains his eye for clear, choreographed actions and fast-paced editing that keeps the audience on edge, but he also escalates the tension through character and theme as has never been so strongly seen within the series. While the two characters start out as uneasy combatants, only agreeing to work with one another in agreement of their mutual destruction, Max quickly begins to help these women.

His help, of course, arrives in the form of a series of jaw-dropping chase sequences—each of which builds and manages to top that which came before it. After a chase from creatively inventive “spiky” cars, Miller catapults the chase into an epic sandstorm where the environment is as much an antagonist for Max/Furiosa as their pursuers. He switches from the awesome, grand scale of the sand storm to the close, hand-to-hand combat fight between Max and Furiosa. This is followed by a chase from grenade-throwing cyclists, then a chase in the stark blue night of the Wasteland…so on.

In each scenario, Miller utilizes every premise imaginable for yet another reinvention of a common chase sequence. From fending off grenade-throwing bikers, to being stuck in the mud, to the pole-swaying kidnappers that populate the ineffably amazing final chase, Max and Furiosa realize that there only chance of survival is to trust in one another. Though the first half is clearly designed as a non-stop thrill ride based purely on survival and escape from Immortan Joe, the War Rig’s arrival at the “Green Place” alters the narrative trajectory toward themes of grander purpose. After now finding that this utopia of women and vegetation has long gone to the ravages of the Wasteland, Max, Furiosa, and the Vulvani women resolve to venture back the way they came: back toward the Citadel.

Additionally, Miller introduces the character of Nux—a warboy convert to whom Max previously served as the blood-bag but has now turned to help their cause. No supporting character has ever had as transitional an arc within the Mad Max realm as Nux, who further highlights themes of cooperation seen throughout the piece. As he later risks sacrificing himself toward the cause for which he was previously fighting against, his addition to the gang in their return across the canyon injects yet another layer of tension toward the finale and Miller’s ability to use the arcs of the protagonist to elevate the depth of the action.

While most filmmakers believe that raising the stakes can only be found through the introduction of new effects, new plot lines, bigger villains, etc., Miller proves that by continually increasing the emotional stakes and the dangers of what is already known—in additional to the pulse-pounding and innovative final chase sequence back through the canyon—how Fury Road manages to make such an action scene so compelling beyond just its action scenes. These are sequences where the stakes of more than just their mere survival are at stake—but in toppling oppressive ideologies that have haunted this region—not to mention their only individual hopes of redemption at stake. From Max’s hope to help save someone, as he does with Furiosa in donating his blood (as his flashbacks repeatedly show his failure to save a child), to Furiosa’s hope for redemption in toppling Joe where she failed before (as demonstrated by the Immortan Joe brand on her neck), to Nux’s hope for salvation in death, all of Miller’s protagonists are given satisfying resolutions to their individual problems—while in the midst of a death-defying chase across the desert canyon.

As Max helps complete his own arc toward becoming a man again, removed from the bestial animal at the start of the film, he finally confesses that his name is Max—having learned that it does matter—before he disappears back into the Wasteland. A man who has found some form of redemption through helping others achieve their redemption, as well. Though these themes are there beneath the surface, Miller never sacrifices storytelling or entertaining action sequences to spell them out for the viewer. Instead, as he always done, Miller uses all his tricks at his disposable to push the boundaries of action filmmaking to their furthest extent. Mad Max: Fury Road—though littered with grand spectacle and special effects—never forgets its tradition of using a simple premise to indulge in the most spectacular array of action sequences possible. Moreover, like Max, George Miller proves why this all matters. He shows how powerfully well-constructed action set pieces propelled by emotionally thematic ideals only enhances the destruction on screen—demonstrating why this character, franchise, and its director—why the world of Mad Max at large…has mattered to so many fans for so many years…and how Fury Road upholds this tradition for the legacy of the series.