Season 1, Episode 1: “The Long Bright Dark”

The recaps for this series can now be found here:

https://nickyarborough.substack.com/p/true-detective-season-1-episode-1

RECAP

1995

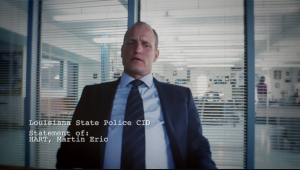

“The Long Bright Dark” opens with the shadowy outline of the killer. The killer affixes the corpse of the victim— soon be known as Dora Lange—in a kneeled praying position to a tree, then sets fire to one of the bird traps, before then setting fire to the surrounding brush—allowing for an expansive shot of the fire across the Louisiana horizon. The next morning, Detectives Marty Hart (Woody Harrelson) and Rust Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) arrive upon the scene to investigate the murder:

Dora Lange is shown brutally murdered: her skin discolored, her hands fastened in a gesture of prayer against the tree, a crown of antlers adorned upon her skull, blindfolded, and the mark of the Yellow King tattooed upon the small of her back. Cohle takes meticulous drawings and notes within his ledger—an enormous notebook that earns him the nickname “Taxman”. Meanwhile, Hart and the rest of the state troopers attempt to understand the gruesome scene.

After, Hart invites Cohle to dinner with his wife and the Taxman accepts—despite the fact that it is his (dead) daughter’s birthday and the Dora Lange scene has clearly disturbed him to some degree. On the car ride back to the office, Hart questions Cohle’s philosophic viewpoint on the world to which the latter replies that he considers himself:

“A realist, in philosophical terms: a pessimist…[which] means I’m bad at parties”. The only symbolic significance to the crucifix in Cohle’s otherwise spartan room is in his use of the cross as a means of meditation—he likes to contemplate the moment in the Garden and the idea of blessing your own crucifixion. Cohle further expands upon his philosophy that: “Human consciousness is a tragic misstep in human evolution…we are things that labor under the illusion of having a sense of self”—eliciting more stern glares from Marty.

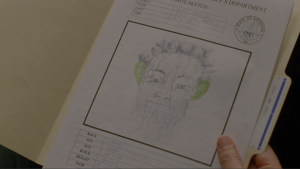

Later, the detectives take to the street for their investigation: learning about the disappearance of the Fontenot girl years back, the “report made in error” when inquiring to Sheriff Ted Childress about the missing girl, and are given the first drawing of the “green-eared spaghetti monster”, as per the girl’s description. They also meet Dora’s ex-boyfriend Charlie Lange, who sheds little light except to say that she “met a King”.

Back at the office, Hart commends Cohle’s investigative work to Major Ken Quesada (Kevin Dunn), while the rest of the office continues to (facetiously) ponder the symbolic meanings of the Dora Lange scene. Afterward, Cohle takes off to meet with prostitutes that may have known Dora at a local bar. There, he asks one of the hookers for barbiturates—citing his inability to sleep. This line serves as a great transition into the next scene, where we first meet Maggie—Marty’s wife—as she finds her husband asleep in his chair and late for work.

Rust later shows up at Marty’s home for dinner—incredibly drunk. Though Marty tries to get his partner to leave upon arriving, Rust decides to stay after striking a conversation with Maggie: a point of contention that will pay off to devastating effect in later episodes.

The next morning, Rust slaps investigator Steve Geraci (Michael Harney) when he calls Rust a rat. A word that would inspire much hatred from a man who just spent a number of years working undercover and is clearly scarred by the experience. Soon after, the Major introduces Reverend Tuttle to the detectives and announces the creation of a Task Force intended to take over crimes with “Anti-Christian connotations”.

Finally, Rust and Marty investigate the former Fontenot residence of the missing girl. There, they meet the girl’s mother and paralyze uncle. While investigating, Rust finds a bird/devil trap exactly like that left at the crime scene of Dora Lange.

2012

A close-up of an open camera begins the series of interviews between Detectives Papania and Gilbough and the 2012-versions of Rust Cohle and Marty Hart. The former two detectives are questioning the latter about the death of Dora Lange in 1995—citing the destruction of evidence caused by Hurricane Rita. The two are particularly interested in what Marty has to say about Rust, especially since their split in 2002. Hart narrates his initial encounter with the Dora Lange murder and his initial impressions of his partner, Rust Cohle: “Well, you don’t pick your parents and you don’t pick your partner…out of Texas…rawbone…edgy”.

Next, the first interview of 2012 Rust reveals his disheveled appearance in the intervening years. Rust demands to smoke and drink a six-pack “because it’s Thursday and it’s past noon” (whose actual drinking motive will be revealed by the end of the interviews.) As the inquiries drag on, and Rust continues to prod them with questions of his own, Papania and Gilbough finally reveal the true intent of their interrogation: there has been another murder in the Lake Charles area.

The detectives hint at the fact that Rust and Marty had supposedly captured the killer in ’95, so these interviews are meant to better help their efforts toward ascertaining any clues as to the current murder. Which prompts Rust’s final line: “then start askin’ the right fuckin’ question.”

———————————————————————————————————————————–

REVIEW

(Spoilers All)

More than anything else, “The Long Bright Dark”—the first episode of True Detective’s first season—does an exceptional job of subtly hinting toward the show’s final horrors while establishing the thick atmosphere of dread that saturates the series’ every moment. The pilot, especially, performs a remarkable job balancing the multiple timelines, establishing the identities of the detectives, and drawing the viewer in with an a number of questions left hanging for the audience to ponder.

Obviously, the identity of the serial killer being the most prominent—but several others are invisibly weaved into the narrative through the ingenious use of the interview device that allows the audience to re-experience the crime through the jaded eyes of the former detectives, where what is left out of their voice-over is often more intriguing than what is said. What caused Marty and Rust’s 2002 split? What led to Rust’s ridiculously disheveled appearance in the intervening years and his quitting the detective career (especially after clearly being such a successful one?) Did they not catch the killer? Why are Papania and Gilbough so interested in Rust?

Most importantly and impressively, these questions are mostly about the characters—not the case itself—that draw the viewer into the series. Writer Nic Pizzolatto and director Cary Fukanaga wisely eschew the expected format of the serial killer drama—one that often indulges in the sadism of the killer—and instead uses the vehicle of the murder to explore the fascinating interior lives of these two very broken men.

Nonetheless, the actual Dora Lange murder remains amongst one of the most evocative and memorable murders portrayed on television. Despite the brutal and gruesome nature, the scene never wallows in the cruelty of the crime. The entire scene is shot with an aesthetic that favors a poetic quality detached from any tinge of exploitation. Every shot within the scene is composed with a sense of mise-en-scene at its best—one that demonstrates the show’s strongest qualities of atmosphere, tone, and subtlety as embodied in the portrayal of this murder that has evolved into the show’s most iconic visual moment.

The interviews, as well, reward repeated viewings for their hints toward events to be explored in greater depth in upcoming episodes. Marty reiterates that he believes, when discussing Rust, that “past a certain age, a man without a family can be a bad thing”. As is revealed down the road, Marty becomes a shell of himself after his wife’s affair with Rust—making Marty the man without a family that he so defends against in these initial interviews.

Moreover, when Rust joins Marty’s family for dinner in ’95, there are a number of small details interesting in lights of later events. Marty’s daughter voices her complaint of broccoli to which Maggie reprimands her to: “mind your matters”. It’s a tiny, quick moment—but one already hinting that Audrey is going to be the rebellious daughter of Marty’s ire in the near future. Rust and Maggie’s chemistry is also on display. Along with her line about insisting on meeting him: “Your life is in this man’s hands…of course, you should meet the family”.

This line rings with especial resonance in light of the fact that Rust does indeed save Marty’s life in the finale when blowing off the killer’s head while his fingers are wrapped around Marty’s throat—his life literally saved by Rust when it was in the hands of Errol. Simultaneously, however, Marty’s life does end up going down a much darker path after his split with Rust—a split caused by his meeting Marty’s family and the sexual affair with Maggie.

While Rust is undoubtedly the star of the show for his idiosyncratic personality, the show does a clever job mixing in the details of his past, his distinct philosophical viewpoint, his strong sense of ethos, and his haunted personal past to portray this unforgettable character. Much has been made in other critical reviews of Rust’s long-winded, “cynical” monologues expanding on his view of human nature. Though these beliefs are explored to much better great depth in later episodes, they actually serve as great comic relief in this initial episode—with Marty’s “stop saying odd shit” as perhaps the pinnacle of their back-and-forth that injects some much needed humor into the episode.

Nonetheless, one also gets a strong and immediate sense of Rust’s unyielding ambition and personal code when called a “rat fuck” by their colleague Steve Geraci—causing Rust to slap him in front of the entire department. Rust’s past working undercover in Texas—as informed by Marty’s voice-over and the tattoo across Rust’s forearm—shed light into why being called a “rat fuck” would remark would elicit such a hostile response. Rust expands upon the horrors that working undercover had upon his psychology in Episode Four, but the fact that his files have been redacted and his disheveled appearance in 2012 help highlight how personally he would take an insult of being called a rat after years working against this identity undercover. The fact that Geraci would be the one to call Rust a rat is especially ironic in considering the fact that Geraci later becomes a rat to the Childress clan in cutting short his investigation of the Fontenot girl—and then a rat to Rust and Marty when they threaten to torture him for details about the Sheriff Childress.

Lastly, and least importantly, this first episodes gives the smallest clues as to the sprawling and expansive details linked to the crime. The episode introduces Sheriff Ted Childress and the “report made in error” about the missing Fontenot girl—a fact that will open much more damning ramifications in later investigations. The episode also gives the earliest hints to The Yellow King—with Charlie Lange stating that Dora had mentioned before her death that she was going to become a nun and had “met a king”. Secondly, Childress’ drawing of the “green-eared spaghetti monster” gives the first visual clue into the identity of the killer. And later at the office, Rust and Marty are first introduced to Reverend Tuttle in his conception of the Task Force created to focus on crimes with Anti-Christian connotations: an act that becomes a point of contention for Rust, and a future piece of further evidence in deciphering the Tuttle/Childress connection with the crime.

Near the end of the episode, when Rust and Marty visit the Fontenot residence, the lighting paints the scene with a patina of gold from his point-of-view. As Rust hints toward earlier, he is prone to auditory and visual hallucinations as a result of his synesthesia condition and this visual saturation of the Fontenot residence in yellow light might be interpreted as further linking the house with what will eventually become the ultimate evidence for the detectives in uncovering the Yellow King.

A phenomenal debut episode. Not just for the series, but television in general. One that introduces its intentions to reinvent expectations of crime fiction in television as a means of exploring large thematic ideas of violence and as an introspective character study with these two detectives at its center, while also offering the audience just enough expository details to come back next week and engage with the show on a more critical level—following Rust’s advice to start “asking the right fuckin’ questions” for future episodes.