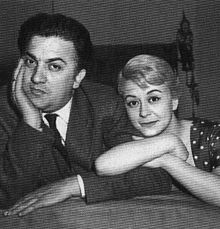

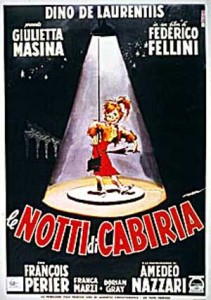

Despite a career spanning twenty-three films as writer and director, filmmaker Federico Fellini once wrote that the only character who still continued to worry him was that of Cabiria—portrayed by his wife Giulietta Masina—in the eponymous Nights of Cabiria. He wrote:

“Cabiria is a victim, and any of us can be a victim at one time or another. Cabiria is, however, more of a victim personality than most. Yet even so, there is also the survivor in her. This film doesn’t have a resolution… so definitive that you no longer have to worry about Cabiria. I myself have worried about her fate ever since.”

Although the director is credited for creating some of the most memorable moments in cinema, along with equally compelling characters, Cabiria stands apart from her cinematic siblings and deserves closer consideration. For Cabiria is a character of contradictions. A prostitute. A cynic. Naïve. Disgusted by men. Desperate for true love. In love with life then begging for someone to kill her…but still, she survives—and she smiles.

Though Fellini initiated his career as one of the preeminent figures within the post-war movement of Italian Neorealism—credited as a cowriter on Rossellini’s seminal Rome, Open City—his early films remained rooted in this realm of storytelling: offering more grounded, character-centric stories concerned with those disenfranchised peoples pushed to the fringes of society. Consequentially, the fates of these characters often end tragically—not washed in fabricated melodrama, but powerfully depicted with pathos and poignancy. Evolving as an artist, Fellini transitioned further from this grounded reality and ventured toward vistas of fantasy and surrealism that still reflected the honest character work seen in these earlier Neorealist films, yet were willing to depart from the unyielding aesthetics to which the emotions of that post-war movement were so strongly responding.

Nonetheless, the film that stands as the transitional point bifurcating between these eras in Fellini’s filmography can be credited towards Nights of Cabiria. For although the film dabbles in surrealism, the heart of the movie still lies in the harsh setting for its titular character to negotiate with a life of unforgiving circumstance. A life that offers as much joy as it does tragedy—one that brings her to the brink of ecstasy, then nearly drives her to throw herself off a cliff.

The episodic structure of the film further complements this idiosyncratic character with an opening scene that serves an intriguing glimpse into the unpredictable nature that composes Cabiria. After her boyfriend Giorgio escorts her to a lake, he pushes her in to drown then steals her purse. Although saved by the locals, she offers no gratitude—angrily storming off instead to search for Giorgio and her money—and creating quite an impression upon the audience of this unusual little woman.

Returning to her little home in the industrial wasteland outside Rome, still enraged by Giorgio, Cabiria seeks out her best friend and neighbor—Wanda. She asks: “Someone would throw you in the river for 40,000 lire? Drown you for 40,000 lire?…Someone who loves you” To which Wanda laughs: “What love? You met him a month ago. You don’t know his name or where he lives. Can’t you understand? He pushed you in! He pushed you in the river!”

Cabiria’s oscillating emotions emerge as the defining elements of her character in each chapter. Mostly, the two major reactions to men seen in this opening sequence: an innocent, child-like yearning to be love, which, after being met with horrendous results, often transforms into defensive anger toward those that ridicule her. As will become evident in the ensuing episodes, and despite warnings from the likes of Wanda (“Can’t you understand? He pushed you in the river!) Cabiria cannot help but revert to these innocent hopes and desires—hopes that the men she meets continually crush.

That night, Cabiria joins her fellow streetwalkers at the Archaeological Passageway and the weird sense of both camaraderie and rivalry within strange menagerie becomes quickly evident. Cabiria, especially, seems to evoke a unique sense of simultaneous ire and fellowship from her co-workers, who seem as equally annoyed as captivated by her presence. Following a spat with these girls, Cabiria is given a ride into town, where the driver offers her the advice that she needs to find a good man, to which she replies: “Why should I slave for filthy pigs like you?” Just moments later, in typical Cabiria-contradiction-fashion, a famous movie star beckons Cabiria to join him within a nightclub (after a fight with his girlfriend)—and she dutifully follows.

Following their fun at the club, and with this famous movie star Alberto Lazzari fascinated by Cabiria’s peculiar personality, he invites her back to his mansion. Cabiria soon finds herself being served lobster and caviar in bed by a butler and is beside herself. She even asks Lazzari for an autograph so that she may brag about the affair to her friends. When Alberto asks about her, Cabiria offers an answer filled again with a combination of defensive explanations, childlike pride, and an unfiltered thought-process that gives further credence toward her almost child-like sensibilities:

“I work the Passeggiata Archeologica. Much more convenient…My friend Wanda. She lives there too. But I don’t bother with the others. The others sleep under the arches in Caracalla. Mind you, I have my own house…with water, electricity… every convenience. I got everything. See this one here. She never, ever slept under an arch. Well maybe once. Or twice. Of course, my house is…nothing like this. But it’s enough for me. I like it.”

During this seemingly fortunate turn of events, Alberto receives an urgent call from his girlfriend that soon finds her intruding upon his tryst with Cabiria. He begs Cabiria to hide in his bathroom, promising that he will soon be back after ridding themselves of the interruption…only for Cabiria to end up spending the rest of the night locked inside the bathroom of this famous movie star with only his pet dog for company.

Like the other sequences of this episodic structure, this chapter functions almost like a short story about a woman’s-would-be-night-with-a-movie-star suddenly injected into a character driven feature length-film. The sequence has a clear beginning, middle, and end and delivers a range of emotions—from the joy of something good finally greeting Cabiria, to the humor of her experience, to the eventual heartbreaking tenderness of her spending the night with this pet dog—isolated, locked away, and forced to sleep on the bathroom floor.

After sneaking away in the morning, Cabiria’s next episode—a scene originally excised in the initial theatrical cut after being condemned by the Catholic Church—involves her coming across a “Good Samaritan” who visits downtrodden citizens living in the caves with food, supplies, and company. While accompanying him, Cabiria comes across a prostitute that she recognizes—a formerly beautiful prostitute admired by every man, but who has now aged into a haggard old woman living in a cave. Immediately, Cabiria recognizes the unbearable truth—her face unable to disguise her sorrow in understanding how such a formerly beautiful woman beloved by men could now spend her remaining years living in the caves beneath Rome—a glimpse of a fate not inconceivable for young Cabiria to one day be living.

Following this episode, Cabiria seeks for something profound—something that may help alter her lifestyle for the better, so she turns to religion—begging the Madonna for help. Though some of her peers appear to pursue this religious quest out of duty more than some deeply spiritual need, Cabiria genuinely pleads for help. She begs: “Madonna, help me, to change my life…make me change my life”.

In credit to Masina’s big doe-eyes, the scene takes on a endearing quality that draws out the innocence inherent to her deeper nature, depicting a young woman incapable of fixing those circumstances of her life, who has reverted to begging for help from a higher power that may be capable of changing qualities of her soul where she cannot.

Not much later, following a few drinks, Cabiria grows quiet in the company of her friends. Impatient, and unable to conceal her rage, she complains: “We haven’t changed! Nobody’s changed”—feeling that her prayers have gone unanswered and that she remains imprisoned within this bleak existence of unforgiving circumstances. Wanda and her friends, however, can only laugh at Cabiria’s infant-like temper—an anger brewing out of the fact that, like a child, she had hoped a god would grant her wish in some Santa Claus like fashion. Flooded with frustration, Cabiria storms off.

Eventually, she finds herself intrigued by an advertisement for a magic show and decides to buy a ticket. Seated in an aisle of mostly men, the magician calls for her to participate in his next act onstage. Though she protests, the men cajole her into cooperating and she begrudgingly joins the magician onstage. After a round of crude insults from the crowd, Cabiria starts to proudly defend herself by announcing that she has a bank account and house of her own—a confession that will ultimately doom her.

Nonetheless, despite this heated exchange between Cabiria and her audience, the magician calms her down enough to perform the trick…and completely hypnotized Cabiria. In one of the film’s most rightfully famous and spellbinding of scenes—one that stands as a true testament to the power of both Fellini as a director and Masina as a performer—Cabiria becomes fully transfixed into the fantasy of her hypnotized spell. The hardened shell of her complicated character that the viewer has grown accustomed to, the defensive little woman with a fiery temper, melts away to expose a wounded, vulnerable soul. She enacts a fantasy wherein she meets an imaginary man named Oscar, confesses her desire to be loved, and the fantasy of living in a loving relationship.

After the rollercoaster ride of her experiences and unpredictable personality, the astounding sequence suddenly stills the viewer into an a deeply absorbing moment that becomes almost too intimate to bear, as the audience is admitted a deeply personal glimpse into the essence of this character’s psyche, only to find the wounded soul hiding beneath the hardened exterior carefully cultivated to protect Cabiria from pain. Then, she is snapped out of her spell.

Wide-eyed and completely disoriented when returning to reality, she is met by jeers from the rude audience of men, laughing at her involuntary confession—and compelling Cabiria to flee.

On the street, however, she is stopped by a persistent fellow. He introduces himself as an accountant—one incredibly infatuated by Cabiria and her hypnotic display. Instinctively fearful of yet another humiliation, she refuses to acknowledge him, but he does not give up. Instead, he again tries to explain how deeply touched her genuine innocence affected him. Moreover, he reveals that his name is Oscar—the name of the man that Cabiria loved in her fantasy—and that he truly believes that the hand of fate has manifested itself in their meeting. Though Cabiria remains suspicious, she agrees to meet him again.

During their next rendezvous, Cabiria continues her cautious engagement with this persistent fellow. Oscar, meanwhile, only appears more romantically transfixed. He professes his love, charms her, and makes clear his intention to continue the relationship. These overtures slowly start to seduce Cabiria, and she can hardly suppress her feelings for her new suitor. Nonetheless, when describing this seemingly perfect new man to Wanda, her friend can only question his motives, though Cabiria remains unphased by such hesitations in the face of finally finding some form of happiness.

On her way home, she encounters a priest, one who advises her toward marriage: “Girls should get married and make children. Matrimony is a sacred thing. In the grace of God.” The admonishment appears to strike a chord, and on her next date with Oscar, she asks that they consider ending the relationship—worried they may be wasting their time. And so, Oscar proposes to marry Cabiria.

She can hardly contain herself in the aftermath, offering a laundry list of criticisms instead: “Marry me? Marry someone you’ve seen ten times? Someone you’ don’t even know. That’s not how it’s done…” But Oscar remains calm—and persistent—and she boils over into an emotional frenzy. Her voice straining, unable to sedate her enthusiasm:

“What do you know about me? About who I am? You shouldn’t fool someone this way. Why pick on me of all people?” At the end of this passionate diatribe, Oscar calmly responds: “We are two lonely creatures. We have to stick together. I need you.” At last, Cabiria accepts. This woman prepared to swear off men just a few night before has now swung to the opposite side of the pendulum—embracing the joy of finding that connection that she so desperately wanted but kept hidden after years of being humiliated or devastated by the eventual outcome.

Completely immersing herself toward living this new life, she soon sells her house to a poor family desperately in need of a larger home—a possession that Cabiria has long prided herself upon as perhaps her biggest accomplishment in this world. Though she freezes for a moment in handing over the keys, realizing the symbolic importance of passing over the prized property as the transitional point from her old life to the new, Cabiria stares upon the faces of this downtrodden family and can then recognize her satisfaction in being able to relinquish the key for the future happiness of this family. Finally, about to step onto the bus that will allow her to leave, she bids Wanda farewell with a smile, promising: “you’ll get a miracle like me”.

The final episode begins with Cabiria at dinner with Oscar, her new fiancé. And while Cabiria can hardly suppress her exhilaration, Oscar has suddenly grown shy and reticent. During their discussion, Cabiria explains that she has withdrawn 40,000 from the bank and plops some of the money there on the table—only to have Oscar promptly scold her to hide it from public view. Not much later, Cabiria suddenly starts to cry tears of joy—thanking Oscar just for liking her for herself and never challenging her about her finances or how she acquired them.

Though Oscar acts more and more withdrawn compared to Cabiria’s increasing adorations, he soon suggests that they take a walk into a secluded, wooded area. Alone, Cabiria showers him with more praise and thanks—a young woman lost in a haze of love. Still, Oscar only behaves visibly nervous, his hesitation palpable and uncomfortable in juxtaposition to Cabiria saying: “ You suffer, you go through hell…but then happiness comes along…You’ve been my angel.”

Oscar then escorts her to a cliff overlooking a lake below—the two of them completely alone upon this isolated promontory. With Cabiria standing on the edge of this cliff, she suddenly realizes how nervous, pale, and anxious Oscar has become. Then, understanding everything in one horrible moment—that Oscar intended to kill her and take her money—Cabiria breaks.

She throws herself to the ground, sobbing, inconsolable, and now begging for him to kill her. Cabiria unable and unwilling to contend with Oscar’s betrayal—humiliated beyond compare after believing she had finally found happiness—and transforms into a being overwhelmed with despair. Confronted by his cowardice, Oscar wastes no more time—he steals her purse and flees—leaving her collapsed, inconsolable, and alone.

Some time later that night, after Cabiria has collected herself from the misery of the experience, she manages to stand back up and walk away from the cliff. She ambles out of the woods and finds herself on a rural street. Moments later, she hears music coming from a group of young men and women emerging from the woods and sharing the road alongside her. They encircle her—clapping, singing, and creating a parade for her—celebrating Cabiria for no specific reason at all: just for being Cabiria.

Despite her desolation, her utter anguish from just hours before when she was begging to die from the unbearable pain—she slowly smiles through the tears…and the film ends.

That smile, however, stays with the viewer long after the credits.

Like the previous episodes, the writing and performance weave a story that impresses a wide-spectrum of emotions along the human experience—from ecstatic highs, to tender poignancy, to the hope of change, to devastating lows that veer close to complete defeat—and yet, Cabiria emerges from each chapter with an enriched understanding of the human experience, whether she is aware of it or not, as does the audience.

Not unlike Antoine Doinel’s final stare at the end of 400 Blows, this concluding image resonates for the lingering ambiguity that demands for the viewer to impress his or her own meaning upon that smile and its implications for Cabiria’s future. Unlike Doinel’s stare, however, that smile cannot help conjure a powerful wave of emotion upon the viewer in that immediate moment—to watch Cabiria resurrected from the utter brink of despair, genuinely pleading to be killed rather than live with the humiliation of Oscar’s betrayal, a kind of trauma that could spiritually paralyze her—and then for her to be able to smile at this improvised parade is a feat on the part of Masina and Fellini that exemplifies the moving power of cinema at its best.

Though the smile of that moment at least gives the audience some hope toward Cabiria’s future, one can understand Fellini’s worry, as well. This is a character that will clearly continue to experience all of life’s highs and lows, perhaps to even more devastating effect than before if it is possible, but that ending still leaves enough hope, enough proof, that no matter what happens—she can still smile again.