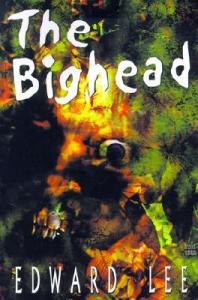

The Bighead—along with the rest of Edward Lee’s novels—have long held an infamous spot within the dark shelf of the horror genre known collectively as the “splatterpunk”. This subgenre distinguishes itself from its horror siblings by—and it bears repeating that this is within the horror genre—excessively graphic depictions of violence and gore. The Bighead itself has long held a reputation as something of a dare for genre readers—a book filled with countless descriptions of the most gruesome, nauseating, stomach-turning scenes of sex, violence, and horror.

From the very first sentence, the reader is able to quickly gauge whether they have the stomach to power through three hundred more pages filled with similarly grotesque sentences or not. This is not the type of horror that haunts you. That is, the type of weird horror that weaves a strong atmosphere of dread before a Lovecraftian glimpse into voids of indescribable terror, nor is it the type of nauseating and vivid horror mastered by guys like Jack Ketchum and Richard Laymon, who tell a strong, suspenseful story of terrible and gruesome acts with characters that—although often detestable—are still recognizable as human beings.

Instead, Edward Lee kicks it up to eleven in nearly every category. Often employing a colloquial prose in chapters concerning either the Bighead or the two deplorable redneck hillbillies Tritt and Balls, the writing simultaneously places the reader within the very uncomfortable skin of the two despicable killers while also putting the vile actions at arms length from ever experiencing some of these over-the-top murders in any realistic way. In other words, this colloquial verbiage allows the reader a glimpse into the Bighead’s mindset with passages reminiscent of something akin to a serial killer’s diary, while also distancing any plausibility of how unbelievably over-the-top such savagery could ever be.

If Lee were to write these passages with a straight face, employing the normal prose utilized in chapters with the “normal” character (Chastity, Jerrica, the Priest), the tone would drastically shift from the more pulpy and self-aware disgust into horrors that would become too comically disgusting to bear. While many would (perhaps rightfully) argue that these never-ending descriptions of creative disgusts are already “too much”, this change in perspective using the “hick” dialogue within the prose serves its purpose for both tone and narrative in a unique and stylistic method.

For readers seeking out The Bighead for a thrill, to test boundaries of good taste and violence, then the book certainly delivers. Moreover, these elements are satisfied within the first fifty pages or so, which make the next couple hundred more tiresome than they should be. The reader becomes accustomed to the rhythm of the book, knowing that after one or two quiet scenes that usually consist of character finding out expository plot details, the next chapter or two will be louder than hell and fulfill its task of topping the previous disgusting scene with even more creative and perverse way to send shivers up the readers spine. Certain elements of the ending may serve as a point of dispute, but by that point, arguments toward the overall quality of the book should more or less be rendered mute.

Still, The Bighead lives up to its reputation for those interested. The novel is filled with some of the most perverse, disturbed imagery that one can imagine, and though this is more for shock and thrill purposes, than any type of horror that will crawl under your skin, one should seek out the novel at least to be a part of the discussion and claim to have powered through the infamous novel. Certainly recommended to fans of the horror genre, and those looking for a book that will illumine its most vile corners.