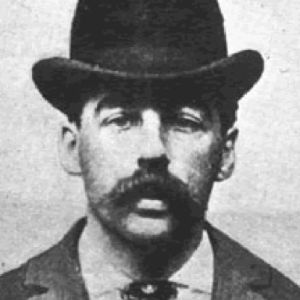

“I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing”

–H.H. Holmes

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood”

–Daniel Burnham

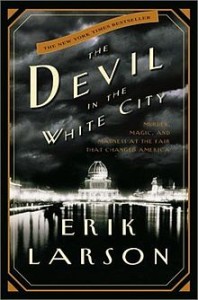

Erik Larson opens his book with these two quotes that function as a preview—and microcosm—to the essence of the two minds at the heart of his Devil in the White City. More than that, both men operated within the same city that spurred their minds to blossom in all their respective depravity and grandeur: Chicago. And more specifically, the author examines the single event that acted as the crucible for revealing both the best and worst that these men could conjure—that event being The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893—an event that would serve as a symbol to the spectrum of the human spirit in all its glory and monstrosity upon the advent of the twentieth century.

Chicago of 1893 was a burgeoning American city determined to demonstrate itself against its metropolitan rivals to the East. And with the national decision to commemorate Columbus’ 400th anniversary—coupled by the renowned debut of Eiffel’s Tower at the recent Paris Exposition of 1889—America needed to utilize the upcoming Chicago World’s Fair as a monument and announcement to American’s unparalleled capacity for achievement and innovation.

Leading this endeavor would be Daniel Burnham—the architect responsible for overseeing its exhibits, maintaining production, and selecting the fellow men responsible for elevating the Fair into a phenomenon surpassing all expectations. After the death of Burnham’s professional partner, celebrated architect John Root, almost the entire burden of the assignment fell upon his shoulders. A task with the potential to cripple most men faced with the challenge, but one in which Burnham would work tirelessly to succeed—despite certain failures and shortcomings often out of his control—to exemplify the power of a determined mind coupled with an unceasing work ethic.

These obstacles of Burnham’s contention would often arrive in the form of inclement weather, bureaucratic battles, and internal squabbles with fellow department heads. Nonetheless, despite numerous delays and last-minute fixes, the Fair was a triumphant success. One that would leave behind such marvels as The Ferris Wheel, Tesla’s alternating electrical current, gum, shredded wheat, spray painting, the device that creates plates for printing Braille…the list goes on ad nauseam. But besides these tangible heirlooms still affecting present American society, the ambition and awe of by the Fair itself would prove to be perhaps its most profound legacy.

As one example, Larson relays an anecdote concerning one of the countless construction workers hired to help the Fair reach its nearly impossible deadline. This construction worker being an otherwise anonymous employee by the name of Elias Disney, who would recount stories of the overwhelming awe instilled by the spectacle of The White City upon the attendees to his young son Walt, which, Larson implies, would later be imitated in his designs of Disneyland.

Interspersed between these anecdotes of American achievement at its zenith, Larson weaves a parallel narrative focused upon the exploits of H.H. Holmes—America’s first true serial killer. Operating his nearby World’s Fair Hotel—which would later be infamously remembered as The Murder Castle—Holmes would seize upon the opportunity afforded by the Fair in the most monstrous manner imaginable: as a vehicle for his plans of murder and theft to be unleashed.

In stark juxtaposition to Burnham’s continued efforts to utilize his resources for the benefit of society, Holmes embodied the nightmare version of the American self-made man. Calculated, cold, and patient, Holmes worked with methodical ingenuity in his construction of the Murder Castle: a three-story hotel assembled from Holmes’ designs that would provide the perfect tenement to his abominable ambitions.

From assigning certain workers to only certain sections (limiting their knowledge to corroborate with one another), to his ability to charm creditors for money that would never be repaid, to his own manufactured public image of a well-to-do businessman that would attract his varied women of interest, Holmes exploited every conceivable aspect of the trusting American public in order to appease the commanding vices surging within him.

These vices would be numerous and varied. From insurance fraud, to theft, to murder, to kidnapping, Holmes existed as a personification of evil. At every turn—with Burnham working relentlessly mere miles away to produce a vision of America that would change and inspire the world—Holmes indulged in every act of depravity that he could conceive. As though possessed (a claim that Holmes would literally attest to after his arrest), H.H. truly lived up to his opening quote of being incapable of quelling his deviant impulses. Whether it was his numerous wives—all naïve women who sought out Chicago in hope of a new life within the burgeoning metropolis—or random hotel guests, or eventually the children of his accomplice…Holmes exhibited no mercy in satisfying the limitless depths of his immorality.

And, as Larson reminds the reader in the introduction, the book is not a work of fiction. Nonetheless, the author weaves this sprawling narrative with compelling and compulsive chapters—each one short and episodic so that the reader falls under the trance of believing that the work could be a fictional, historical thriller. More importantly and impressively, these chapters are written with such specificity and atmosphere as to completely transport the reader into the setting. Larson favors stark, smooth prose that paints a vivid picture of the subject and allows the reader to experience the range of emotions occurring within this revolutionary event: from the majesty of the Court of Honor to Annie Williams’ utter panic after Holmes locks her within a vault, turns on the valve for poisonous gas to be released, and listens to her final screams before death just outside the door.

The last third of the novel—with the Fair inexorably approaching its bleak end and the determined detective named Frank Geyer on Holmes’ elusive trail—Larson escalates the suspense to especially memorable and powerful effect. After Holmes’ many, many creditors finally coalesced to take him down, H.H. escaped from Chicago. However, the hotelier did not flee alone; instead, he absconded with three children belonging to his former assistant: the drunken henchman Benjamin Pitezel. As Geyer tracks Holmes across the northern states, locates him in Toronto, and discovers the gruesome remains of the children murdered and mutilated by Holmes, the storytelling morphs into a riveting chase across America and Canada to finally deliver retribution upon the killer. Geyer’s descent into the cellar of the climactic Toronto home reads with as much suffocating suspense and dread as any horror novel, and the brutal aftermath—wherein the mother must identify her horribly mutilated child at the coroner’s office—delivers the unbearable emotions of devastation experienced by the victim that are often glossed over by similar works in the genre.

By the finale, wherein Larson interweaves the rapid destruction of the Fair following the assassination of Chicago’s mayor with Holmes’ arrest and execution, the author provides perspective on how the immense scope of these events affected the American public. Burnham with the World’s Fair—a prodigious monument to the power of accomplishment in American creativity, innovation, and inspiration; then with Holmes and the Murder Castle—a material edifice containing the darkest conceptions of a man’s mind and a literal house of horrors that contributed nothing but carnage and chaos.

In this striking juxtaposition, Larson underscores how these two men—existing under the same time, place, and tested by the same opportunity—opted to forge the material legacy of their lives. And in demonstrating these expanded boundaries of American accomplishment and depravity upon the advent of the twentieth century, Larson impresses a larger understanding of the scope of human nature; and more importantly, the significance of how each man chooses to actualize his own nature, despite his limited time, and how profoundly the consequences of these actions continue to echo beyond the ephemeral present.

First of all I want to say terrific blog!

I had a quick question in which I’d like to ask if you do

not mind. I was curious to know how you center

yourself and clear your mind prior to writing.

I have had a tough time clearing my thoughts

in getting my thoughts out. I truly do enjoy writing however it just seems like

the first 10 to 15 minutes are usually wasted simply just trying to figure out how to

begin. Any recommendations or tips? Thank you!