Zodiac could not have more storytelling disadvantages working against it. This is a narrative centered around the brutal murders committed by a serial killer over a span of many years, in a number of different locations, who was not only never arrested but whose identity was declared unsolved, and whose most determined investigator proved to be a cartoonist.

Yet, in spite of these potential storytelling obstacles, Zodiac succeeds beyond compare: a meditative movie in the true crime genre that crafts a compelling character study with all the suspense, intrigue, and horror of its genre siblings that never sacrifices the tone or trajectory of its climax in favor of succumbing to those conventions that have sought to define the genre. There are no red herrings, though there are potential suspects who seem the most likely. There is no final arrest that allows for the main character’s validation, though the evidence does lead to a likely suspect and sense of resolution. Loose ends are not tied up. At one point, the case goes cold. And still, Zodiac refuses to bend in offering easy narrative choices. Instead, the narrative transforms the film into one that takes the painstaking time to map out geography, to examine every piece of evidence, to follow false trails, to commit itself toward rightful prosecution—and concludes as an especially unique and rewarding experience as a result.

In an exceptionally well-crafted and memorable opening, the film opens on July 4th 1969. Fincher and cinematographer Harris Savides imbue this introduction with an outstanding sense of atmosphere that saturates every element of the introductory scene with a sense of teenage suburbia—from fireworks flashing across the sky, to two teenagers uncomfortably shifting in a car, to a palpable sense of nervousness found within an isolated lover’s lane—the filmmakers instantly paint a specific portrait of this point in American history. However, the tension-filled arrival of the Zodiac Killer and his brutal attempted murder of both kids instantly shatters any preconceived notion that this film will follow the typical track taken by most true crime thrillers.

Transitioning to a month later, a letter arrives at the offices of The San Francisco Chronicle from this violent killer. Though journalist Paul Avery (Robert Downey Jr.) and the other editors begin their immediate pursuit of the cracking the killer’s code, cartoonist Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) seizes upon the cipher with an almost alarming sense of interest. Though he admits to “liking puzzles”, he snatches upon the opportunity to ingratiate himself into the case at large—which he will continue to do over the ensuing years.

Not long after, the Zodiac’s second cinematic murder befalls a couple enjoying an afternoon picnic near Napa. There are few scenes in the history of horror or crime movies that command a sense of arresting suspense and dread as powerfully as this chilling scene. Calling to mind something along the lines of Haneke’s masterpiece that is the original Funny Games, Fincher allows the terror of the scene to slowly escalate through a sense of real-time that refuses to let the audience off the hook.

And though the actual time frame of the scene is relatively short, the Zodiac’s menacing presence (despite his goofy appearance of actually being a fat, middle-aged man wearing an executioner’s mask and a black bib with a homemade Zodiac sign) the scene’s stillness evokes an authentic feeling of fear. When the Zodiac stabs the couple to death, the brutal murder being portrayed invokes a startling reality that few true crime films are willing to accurately execute upon the screen. The Zodiac continually stabs the victims, unphased by their blood-curling shrieks, and the audience must watch as paralyzed witnesses to this horrendous act.

Nonetheless, the case’s most catalytic murder arrives only two weeks later when the Zodiac murders an unsuspecting cab driver by gunshot. This third crime causes Detective Dave Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) to arrive upon this crime scene that will ultimately compose the remainder of his career as a detective. Screenwriter James Vanderbilt uses the clever technique of marking the years that will pass between these two detectives by always having Toschi greet his partner with a “Happy Birthday”—a simple dialogue exchange that reminds the audience how many years will eventually go by with the the identity of the Zodiac still unsolved.

Though Toschi became quite famous by detective standards, the screenwriters flesh him out with quirks and distinctive character attributes that help humanize him within a version of reality far removed from the alpha-masculine detective and model for Detective “Dirty” Harry Callahan that ultimately cemented his legacy. Instead, this Toschi acts as a determined detective insistent on solving the case through hard evidence and clues, despite numerous bureaucratic obstacles, and who likes wearing his bow ties and chewing his animal crackers. The film also successfully offers a version of the detective character that is not the cynical nihilist, nor the career-obsessed investigator that often the populates the genre—but somewhere in between. All of these qualities, of course, materialized through Ruffalo’s quiet, nuanced performance.

The biggest break in the case arrives in suspect Arthur Leigh Allen. Following a sprawling investigation and extensive cooperation between the various California counties, Toschi and his fellow investigators track down Leigh Allen based on an admission from an old roommate who remembered Allen mentioning phrases that mirrored those of the Zodiac. The ensuing scene delivers an extraordinary cat-and-mouse dance between the detectives and their primary suspect filled with tension and suspense, though completely conveyed through dialogue and an excellent sense of pacing found through the editing. Leigh Allen’s eventual reveal of a wristwatch branded in advertisements as The Zodiac—along with its trademark icon—seems to seal the deal for the investigators.

However, this seemingly obvious solution does not come easy—as one may suspect from the true crime genre. Handwriting experts remain adamant that Allen could not have written the Zodiac letters, and despite Toschi’s insistence that his ambidexterity may be to blame, many of the normal routes prove impossible for progress. Nonetheless, they are able to eventually find a warrant and raid Allen’s trailer in a scene filled with all the hallmarks of a David Fincher movie. Various rodents populate the small trailer, and dark shadows swirling over dusty air confine the characters, while a palpable tension surrounds every second of this suspenseful raid. Still, these determined detectives are unable to find that single piece of evidence that will allow for Allen’s arrest through legal means.

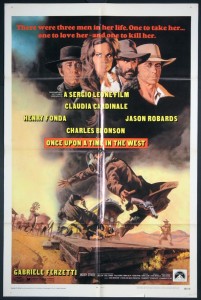

Moreover, the case begins to take on a life of its own within the public sphere in a previously unprecedented way for the San Francisco PD. The filmmakers use these montages to both comedic and informative effect, as nearly every citizen in the city confesses the name of someone that they think may be the Zodiac Killer (at one point, the list of suspects numbers over five hundred). Worse, the media and entertainment industry begin devouring the Zodiac case for their own profit-driven purposes—most famously through its glamorization of the investigation in the form of the Don Siegel/ Clint Eastwood film Dirty Harry. Graysmith even happens to introduce himself to Toschi in the aftermath of the screening, where the latter can hardly contain his visible disgust for the public’s appetite of vindictive violence over any version of justice provided through the American legal system.

Meanwhile, those characters from The Chronicle continue their own parallel developments of the case. Graysmith has slowly entrenched himself with Avery for involvement in the case, though the latter has devolved into deeper spirals of alcohol addiction. But it’s Graysmith’s relentless fascination that will largely drive the latter third of the narrative. His first date with his future wife, Melanie (Chloe Sevigny), proves to be an accurate model for how much of their married life may prove to be—with Graysmith lost in the mazes of his mind cultivated around the case, while Melanie shoulders the familial responsibilities despite her best interests. And at the intersection of these events…

The case goes cold.

Flashing forward a few years, however, Graysmith remains as obsessed as ever. Though more kids have arrived, and his wife appears less supportive than her earlier efforts appeared, Graysmith remains possessed with cracking the currently cold case. He hunts down a much-older Toschi, who has divorced himself from the obsession that drives Graysmith’s being. And while he’s unable to provide Graysmith with any official police evidence due to its status as a still-active and open case, he does tacitly provide contact names with the other investigators involved from years back. As Graysmith’s determination to solve the case under the guise of writing a book begins to collapse more towards mental illness than actual pursuit of justice—to the point that he is forcing his own kids to help in the investigation and an anonymous caller has begun calling his family in the middle of the night—his wife finally breaks and asks for his motivation in solving this crime, to which Graysmith responds:

“I…I need to know who he is…I need to stand there, I need to look him in the eye and I need to know that it’s him.”

As Graysmith’s confession reveals, he needs to find the killer for his own personal resolution of this case that has taken such a toll on his personal identity more than anything else. Now separated from his family, Graysmith remains as determined as ever. His search brings him into contact with the various officers in the various counties previously encountered in the first half—bringing these two parallel storylines full circle—and also allowing Robert to find the man that he slowly realizes may be the Zodiac himself. Despite ultimately being a bit of a red herring, Fincher creates a world of suspense out of this simple scene of Graysmith being invited to this elder man’s home and subsequent investigation of his basement. (At this point, paying off an earlier piece of evidence about basements in California to excellent, tension-filled effect.)

And yet, after a small admission from an inmate that was previously at a party attended by Leigh Allen, Graysmith manages to collate all the evidence to prove that Leigh Allen may be the Zodiac killer. Though Toschi seems impressed, he also cautions Graysmith against his zealous attitude in convicting Leigh with mostly circumstantial evidence:

Graysmith: Just because you can’t prove it doesn’t mean it’s not true

Toschi: Easy Dirty Harry…Finish the book.

And, in an unusual climax that could only occur in a film constructed with as calculated care in its character set-ups as Zodiac, Graysmith tracks down his suspect to a hardware store in Vallejo. Here, he pays off the aforementioned quote to his wife, that he needs to: “stand there, I need to look him in the eye and I need to know that it’s him.”

Graysmith does exactly that. He and Leigh Allen exchange a tacit confrontation of the eyes that ultimately serves as some form of closure for Graysmith in lieu of actual legal persecution. Again, it bears repeating as an example of the commendable craftsmanship on display within this sprawling narrative that the filmmakers made an almost non-verbal stare down between these two men in a random hardware store in Vallejo—one without any cheesy payoff lines, shootouts, or slow-motion gunfights—to serve as a satisfying resolution to a nearly three-hour-long case that still never offers any kind of definitive answer for its opening incident.

Still, the filmmakers include one more scene to bring about an even greater sense of closure by re-introducing the teenager from that opening Zodiac murder as an older man. He, too, selects a picture of Leigh Allen as the man that shot him on that 4th of July Night—solidifying this theory of Leigh Allen as the killer—as the somber and haunting tune of Donovan’s “Hurdy Gurdy Man” sweeps over the soundtrack. A series of title cards shed further light on the final facts of the case and relevant details concerning the characters’ fates—most notably, the fact that Leigh Allen died of a heart attack before he could be brought in for further questions in the aftermath of Graysmith’s investigations.

This is a crime thriller that—like most of its peers—begins with a central mystery, yet dramatically distinguishes itself by also ending with this central mystery. Yes, there are clues and pieces of hard evidence that certainly indicate one suspect more than the others—but this still ambiguous answer refuses to bend facts in order to satisfy either the audience or its determined protagonists. More impressively, however, the filmmakers still manage to imbue a feeling of resolution—despite the actualities of the plot—in order to create an entertaining and though-provoking film that defies the conventional trappings of its genre. In doing so, the filmmakers produced a provocative and compelling film that proved possible how to deliver a narrative that delivers emotionally satisfying results despite those normal cinematic techniques driven by plot.

Moreover, the filmmakers managed to make a film that considered the ripple effect of the crime upon its characters’ nature, more than facts of the crime which serve as perfunctory plot bridges and for deeper explorations into the characters’ psyche . How this crime and its ensuing label as an unsolved crime could warp a good-natured cartoonist into a man capable of tearing apart his family at the cost of finding self-satisfying answers. And how an audience can grow more fascinated by the obsession of its main characters, than by their initial fascination in those horrendous crimes committed by the serial killer at their forefront. In avoiding those normal trappings of the genre, and delivering a narrative that prevails where so many movies would have folded under the weight of normal narratives routes, Zodiac delivers an anomalous viewing experience for the true crime genre. One that seeks to redefine the capabilities of a case rooted in an unsolved reality to find a fresh approach to character catharsis—and successfully succeeds in doing so—allowing for a distinctive and praiseworthy take on the true crime thriller.

Finally, after electrocuting Yeong to death, and after Ryu’s discovery of her corpse, the two men began a tense standoff waiting to murder the other. Ultimately, Dong-jin proves the victor after rigging his home with an electrical trap that knocks Ryu unconscious. Now hauling Ryu back to the lake that proved to be the site of his daughter’s death, the father forces Ryu to undergo that same punishment that engendered his daughter’s death. Though Dong-jin acknowledges that Ryu may be a good man, the father also explains that he has been left with no recourse but to kill him due to balance out the tragedy of his daughter’s death. This leads to the brutal, stomach-turning climax, where Dong-jin hacks off both of Ryu’s Achilles Tendons to induce his drowning.

Finally, after electrocuting Yeong to death, and after Ryu’s discovery of her corpse, the two men began a tense standoff waiting to murder the other. Ultimately, Dong-jin proves the victor after rigging his home with an electrical trap that knocks Ryu unconscious. Now hauling Ryu back to the lake that proved to be the site of his daughter’s death, the father forces Ryu to undergo that same punishment that engendered his daughter’s death. Though Dong-jin acknowledges that Ryu may be a good man, the father also explains that he has been left with no recourse but to kill him due to balance out the tragedy of his daughter’s death. This leads to the brutal, stomach-turning climax, where Dong-jin hacks off both of Ryu’s Achilles Tendons to induce his drowning.