That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees

– Those dying generations – at their song,

The salmon‐falls, the mackerel‐crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

So begins the Yeats poem from which Cormac McCarthy’s novel—No Country for Old Men—takes its name. As detailed in four stanzas, Yeats’ poem addresses man’s mortality: describing a man’s anxieties over his approaching age and encroaching death. The man combats these fears by sailing to the shores of Byzantium, where he hopes that the wise sages from ages past may transcend his soul into the fire of immortality. This fabled Byzantium representing a paradise—an immaterial realm of wisdom and eternity—separated from the deteriorating quality of life found in the material world.

But the country of McCarthy’s story is no paradise.

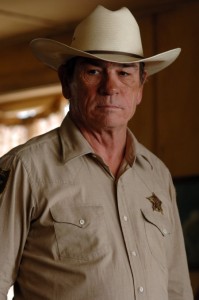

Set near the Texas/Mexico border in 1980, No Country for Old Men instead presents a barren, brutal landscape where the morals and identity of a nation are at a crossroads. The story follows the journey of three characters caught in a tangled pursuit of one another across this burgeoning wasteland: Llewyn Moss, the everyday man responsible for stealing the money that kicks the plot in motion; Anton Chigurh, the philosophical, psychopathic hitman chasing Moss across the desert; and Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, the aging Sheriff searching for both men and painfully aware of the declining moral tide plaguing his small county of Terrell, Texas and rapidly spreading out across the nation.

Sheriff Bell serves as the story’s moral compass—a World War II veteran who inherited the role of lawman from his family, and who finds himself aghast at the abhorrent violence suddenly sweeping throughout the sleepy Texas town. In a significant though obvious change for adaptation reasons, his narration is absent from the film. Yet in the novel, these narrations at the beginning of each new chapter function both to break the relentless charge of the narrative and also allow for the Sheriff’s musings about his surrounding world, which he not only no longer recognizes, but which he may no longer want to recognize.

The audience is first introduced to this world of decline through the opening chapter, where the strange, dangerous hitman named Anton Chigurh brutally strangles a young Texas Deputy by transforming his handcuffs into a substitute garrote—slicing his cuffs through the young man’s neck and splattering blood across the police department floor. He then retrieves his iconic weapon—a captive bolt pistol aka a cattle gun—which drives a steel rod through the victim’s skull before then retracting, leaving no exit wound and ensuring a certain death.

Meanwhile, Llewlyn Moss, a Vietnam vet and welder by craft, spends his time in the isolated terrains of West Texas where he hunts a herd of antelopes within these wide-open and unpopulated spaces. While tracking a wounded animal, he stumbles upon the aftermath of a drug-deal gone horribly awry—multiple Mexican men, their animals, and their armored trucks brought down by a barrage of bullets. During his search, Moss, ever the hunter, finds a satchel of money containing close to two million dollars.

This catalytic chapter serves as an embodiment of the unique style so representative of McCarthy’s aesthetic: prose writing that modulates between being clinically observant to poetic and profound, often within the same paragraph:

“He hiked on along the ridge with thumb hooked in the shoulderstrap of the rifle, his hat pushed back on his head. The back of his shirt was already wet with sweat. The rocks there etched with pictographs perhaps a thousands years old. The men who drew them hunters like himself. Of them there was no other trace.”

The Coens’ cinematic translation of this opening scene works to similar effect: introducing the tone, style, and distinguished aesthetic that separates the film from those typically found in such a genre thriller. Specifically, the viewer becomes starkly aware of the filmmakers’ choice to work with a very limited score—rarely using music at all except in a few instances where its presence serves to subtly enrich the emotional content of the scene, rather than manipulate the viewer toward the desired feeling. While most filmmakers are incapable of wallowing within scenes of long silences for fear of boring the audience, the Coens prove that when armed with a strong storyline and a palpable sense of tension that the manipulative effect of music can often be unnecessary or distracting. Instead, the music of the rustling wind and the crunch of boots across gravel provide a soundtrack that further amplifies the suspense already present within the premise.

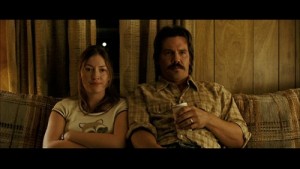

Nonetheless, Moss steals the money and returns to his trailer parker home. There, he banters with his wife, Carla Jean—a young woman emerging from her adolescent naiveté yet charged with enough wit to keep up with a man like her husband, Llewyn. In the book, the age difference between Carla Jean and Moss becomes a much more prominent factor in their relationship. The fact that she is an eighteen-year-old sales clerk that the much-older-Moss decided to marry, despite her mother’s protests, adds a bit more complexity to their marriage than can be seen in the film. Though Kelly MacDonald’s Texas drawl disguises her Scottish roots, the comparative age-difference between the couple made explicit in the novel imbues a bit more tragedy to the fate that ultimately befalls the young woman.

Still, that night, Moss finds himself in a restless quandary. While searching for the money earlier in the day, he encountered a dying Mexican man asking for water, which forces Moss to return to the desert. There are two ways to interpret Moss’ decision: one, that he is returning to give the man water and save his life; or two, that he is returning to kill the man in the case that the Mexican survives and informs upon Moss’ identity to his superiors.

Either way, the hunter returns to this desecrated rendezvous point, only to find that he is no longer alone. A chase throughout the rocky terrain ensues: one that ends with badly wounded Moss escaping into a river. In both the book and film, the spotlights affixed to the trucks produce a unique element of danger that works to tremendous effect. Where the majority of crime thrillers supply drug dealers that veer so far toward the cartoonish as to eliminate any atmosphere of menace, there’s a feeling of imminent doom generated by the presence of these gangsters—and knowing that Chigurh is somehow tangentially connected with them—that causes an otherwise simple chase through the desert into a white-knuckle sequence of suspense.

From this point forward, the story is very much a game of cat-and-mouse between the three characters: Moss on the run, Chigurh hunting him down, and Bell hoping to find either one before more violence can erupt across his county. The Sheriff’s reaction to this escalating violence serves as the spine of the story’s theme. As a veteran of World War II, and a man realizing that the morals with which he believed upheld the fabric of society are disintegrating before his eyes, the Sheriff begins to question the capabilities and purpose of his identity as a representative of the law.

Early in the novel, McCarthy provides a quick scene of Bell’s character that demonstrates the kind of acute character work separating him from most of his literary peers, similarly eliminated from the film due to its inherent novelistic quality and running-time reasons. Although almost less than a paragraph, the scene instantly establishes the attributes of respect and tradition that so exemplify Bell’s character. In the scene, Bell and his Deputy are driving back from the scene of the massacred Mexicans, when he suddenly spots a redtail hawk lying dead and removes it from the road. McCarthy writes:

“He picks it up by one wingtip and carried it to the bar ditch and laid it in the grass. They would hunt the blacktop, sitting on the high powerpoles and watching the highway in both direction for miles. Any small thing that might venture to cross. Closing on their prey against the sun. Shadowless. Lost in the concentration of the hunter. He wouldn’t have the trucks running over it.”

These core values that compose Bell’s character, as a man who lives by a code of black-and-white morals within a society that has promised following such a code will be rewarded, comes to be challenged by the criminal at the center of this narrative:

Chigurh.

Not unlike McCarthy’s most famous literary character—the unforgettable Judge Holden of Blood Meridian—Anton Chigurh appears to personify a dangerous quality beyond the normal capabilities of a man. He is a force of nature. An entity of violence prepared to scour the corners of the earth to complete his task. What separates Chigurh, again, from veering into cartoonish power more along the lines of the Terminator than Judge Holden can be credited to the philosophical propositions that guide his code. Most infamously, this is represented through his flipping a coin to determine a victim’s fate.

Almost an exact adaptation from the scene in the book, Chigurh encounters a hapless, friendly gas station clerk who soon finds his entire life at the hands of this hitman. Despite the clerk’s various approaches to steer the conversation toward small talk, Chigurh relentlessly antagonizes the clerk toward the deeper implications of both his simple questions and the journey of his life that has now brought him to confronting Chigurh. Though the clerk remains clueless as to what he’s putting at stake when Chigurh demands that he call the toss, the implications that he stands to “win everything” and has been “putting it up all his life” instantly saturates the scene with a thick tension that leaves the reader as compelled and speechless as the clerk.

Moreover, Chigurh’s code of violence presents him not as just a mere hitman working at the behest of his superiors’ orders, or one who takes the act of execution lightly, but as a man who views himself as a necessary mechanism far beyond the normal definitions of a murderer. Chigurh represents a destructive force of will—a personification of violence, fate, and determinism that cannot be left unacknowledged or ignored.

Early on, in a quick but insightful character moment, Chigurh drives across a bridge at night. He rolls down his window, draws his gun, and fires upon a bird that just happened to be sitting there upon Chigurh’s crossing. Though darkly comical, the implications that any creature—whether it be a drug dealer, a lawman, convenience store clerk, Llewlyn Moss, or idle bird—any living creature that crosses Chigurh’s path must now contend with the fact that such a crossing may result in their last moment of life. In contrast to Bell’s earlier actions when coming across a bird, where the Sheriff removed the fallen carcass from the road as a sign of respect, Chigurh’s disregard for life of any design knows no bounds.

When Moss later encounters another hitman, Carson Wells, the latter tries to paint a portrait of the danger that awaits him:

“What is he supposed to be, the ultimate bad-ass?”

“I don’t think that’s how I would describe him…I guess I’d say that he doesn’t have a sense of humor…you cant make a deal with him. Let me say it again. Even if you gave him the money, he’d still kill you. There’s no one alive on this planet that’s ever had even a cross word with him. They’re all dead. These are not good odds. He’s a peculiar man. You could even say that he has principles. Principles that transcend money or drugs or anything like that.”

Unlike Chigurh, Wells function as a more proto-typical hitman. He is a company man, hoping to complete his job, get paid, and go home. Indeed, he is a man with a sense of humor—one much more discernible through Woody Harrelson’s stylish performance than may be gleaned from the book. However, the film does delete a thought-provoking scene with Wells that serves as further evidence for McCarthy’s acute ability to weave moments of poignancy, tragedy, humor, and bits of surrealism into one unique scene.

Following a very tense, very bloody shootout between Moss and Chigurh around a hotel that ends with the former bleeding to death and stumbling into Mexico, the latter similarly wounded and forced to retreat back to his motel room, Wells returns to the scene of the incident to perform his own personal investigation of the aftermath. There, following the various bullet holes that decorate the hotel façade, he stumbles into a room where an old woman has been killed by a random bullet expelled during the shootout:

“A rockingchair by the window where an old woman sat slumped. Wells stood over the woman studying her. She’d been shot through the forehead and had tilted forward leaving part of the back of her skull and a good bit of dried brianmatter stuck to the slat of the rocker behind her. She had a newspaper in her lap and she was wearing a cotton robe that was black with dried blood. It was cold in the room. Wells looked around. A second shot had marked a date on a calendar on the wall behind her that was three days hence. You could not help but notice. He looked around the rest of the room. He took a small camera from his jacket pocket and took a couple of pictures of the dead woman and put the camera back in his pocket again. “Not what you in mind at all, was it darling?”

Although one can understand the excision of this small moment from the film, the remarkable little moment evokes pathos in a creative and intriguing manner. The death helps demonstrate the cost of violence upon those not even connected to the central narrative, and the rippling effect of such violence—even for an old woman sitting alone in her hotel room, oblivious to the bloody gun battle raging around her—which ultimately cost the elderly woman her life.

As mentioned, the subtle use of score helps further distinguish these tense sequences punctuated by explosive violence. The Coens employ silence with confident control—silence that imbues a feeling of verisimilitude and increases the unease that saturates these otherwise simple settings. Additionally, Chigurh’s second weapon of choice—a shotgun outfitted with a silencer—produces a particularly eerie pneumatic noise that catches the viewer off-guard in their typical expectation of a shotgun blast.

Besides the compression/omission of Sheriff Bell’s narration, the second largest adaptation change can be found in Moss’ relationship with a young hitchhiker. Although one can understand the filmmakers’ decision to compress the material, these exchanges between Moss and the naïve, young hitchhiker are responsible for some of the book’s most touching exchanges. In the film, Moss merely meets a flirtatious woman outside the motel pool begging to share a beer, which promptly cuts to his and her death just moments later—with the Sheriff watching a band of gun-wielding Mexicans fleeing on a pick up truck.

In the book, however, Moss and this young girl share a number of scenes together: in the car, in a diner, in the motel; and ultimately, in the morgue. These dialogue exchanges bring out shades of humanity to Moss that are missing in the film and which are harder to find in between his scenes of machismo against his enemies or the constant stream of sarcasm exhibited with his wife, Carl Jean. Here, Moss takes on a more paternal role, offering this horribly naïve woman advice and comfort toward the dangerous trek toward California that she has chosen to embark.

In their final scene together—again a significant departure from Moss’ concluding scene in the book—McCarthy manages to inject real poignancy into their relationship and imminent deaths. The two share a final conversation upon the hotel’s porch steps, after Moss has given her a sizable sum of his stolen money, so that she may safely arrive in California. Moss advises:

“Let me tell you somethin’ little sister. If there is one thing on this planet that you don’t look like, it’s a bunch of good luck walkin’ around.

“That’s a hateful thing to say.”

“No it ain’t. I just want you to be careful. We get to El Paso. I’m goin to drop you at the bus station. You got money. You don’t need to be out here hitchhikin’.”

The conversation steers from being overly sentimental, but there is a sweetness to Moss’ blunt advice—warning this young woman away from notions of good luck and the fact that money is her best hope for success in this country—that allows for a scene of quiet, genuine emotion to emerge in the midst of this engrossing cat-and-mouse thriller.

And then Moss and the girl are both murdered.

As in the film, the deaths are actually revealed somewhat after the fact—with Sheriff Bell driving out to the site of the corpses. Having just communicated with Carla Jean, and knowing how devastated the young woman will be upon hearing about the death of her husband, the Sheriff’s face sinks in devastation. From both a literary and cinematic approach, the effect is jarring in the best way possible. With every single chapter told through the point-of-view of either Bell, Chigurh, and Moss, to have the latter killed through the prism of Bell’s chapter creates an unexpected feeling—akin to both experiencing the death firsthand while also hearing about it secondhand, like the viewer should not have been told about it yet, and when coupled with the information about the death of the young girl—creates a very moving and memorable death for Moss.

Reeling from the scene of the massacre and their trip to the morgue to identify the bodies, Sheriff Bell and the local El Paso Sheriff retreat to a diner for some late night coffee. There, the two commiserate over the changing nature of being a lawman and the rising tide of violence that seems insurmountable against their purpose to protect the public. Throughout this scene, much of Bell’s dialogue that serves as opening narration for the major chapters has been reworked to fit the dialogue of these two bygone Sheriffs realizing that they are up against a new kind of darkness—one that they have not previously encountered and are unsure how to defeat, if such a thing is even possible.

Probably the most memorable bit of narration reconfigured for this dialogue comes near the end of the meal, when the two Texas Sheriffs remark:

“It’s all the goddamn money, Ed Tom. Money and the drugs. It’s just goddamn beyond everything…You know, if you’d have told me twenty years ago, I’d see children walking the streets of our Texas towns with green hair, bones in their noses…I just flat-out wouldn’t have believed you.”

“But I think once you quit hearing ‘sir’ and ‘ma’am’ the rest is soon to follow”

“Oh, its’ the tide…it’s the dismal tide. It is not the one thing”.

Though this dialogue is taken nearly verbatim from a separate piece of Bell narration, it reflects another passage where the Sheriff contemplates a similar thematic issue:

“Teachers come across a survey that was sent out back in the thirties to a number of schools around the country. Had this questionnaire about what was the problems with teachin’ in the schools…and the biggest problems they could name was things like talkin’ in class and runnin’ in the hallways…things of that nature…Forty years later. Well, here comes the answers back. Rape, arson, murder. Drugs. Suicide. So I think about that.”

Both these passages reflect the bleak outlook on the imminent future toward which Bell believes he may be receiving just a glimpse of in the present. Though these topics may seem conservative or comically traditional in a political sense—specifically in regards to kids with “green hair and bones in their noses”—the second passage speaks directly to the kind of violence that Bell is witnessing and continues to haunt him. Though, obviously, violence on the level of murder and rape has existed for as long as man’s existence, Bell is commenting on the level of comfort and escalation that he is noticing in his day-to-day duties, especially in regards to his experiences with Chigurh—and the disturbing truth that there may be nothing he nor the law can do to fight against such a dismal tide of violence.

Meanwhile, despite Moss’ death and the retrieval of the money, Chigurh has not extricated himself from the case. Instead, due to an oath upheld between him and Moss, wherein he promised the doomed hunter to spare Carla Jean if Moss would hand over the money and refused, he must uphold his word and kill Moss’ wife. Here again, there is a slight change between the novel and film. Though the conversation remains much the same, the conclusion holds a significant difference.

In both versions, Carla Jean returns from her husband’s funeral to find Chigurh waiting for her with his weapon in hand. Then, despite her protests that “he doesn’t have to do this”, Chigurh insists that he must: due to his oath to Moss.

But Carla Jean refuses.

She demands that Chigurh accept responsibility for the fact that he has a choice to walk away—a view that Chigurh does not share. In a final chance at freedom, Chigurh offers her the same coin toss that he has offered to a number of his victims.

She calls heads and the coin lands on tails.

Sobbing, she refuses to acquiesce to Chigurh’s proposition that he would have obeyed the coin and let her go. But Chigurh counters:

“I have no say in the matter. Every moment in your life is a turning and every one a choosing. Somewhere you made a choice. All followed to this. The accounting is scrupulous. The shape is drawn. No line can be erased. I had no belief in your ability to move a coin to your bidding. How could you? A person’s path through the world seldom changes and even more seldom will it change abruptly.”

Speaking directly to the book’s major themes, he further illuminate his philosophy:

“I have only one way to live. It doesn’t allow for special cases. A coin toss perhaps. In this case to small purpose. Most people don’t believe that there can be such a person. You see what a problem that must be for them. How to prevail over that which you refuse to acknowledge the existence of.”

This idea of existing as an entity beyond the capacity for someone to recognize as something of human nature directly addresses the issues raised by Bell. The Texas lawman cannot comprehend the rising violence, because he refuses to believe that a person can only exist in this one regard—to perpetuate and commit acts of violence—and therefore he cannot prevail over this unnamable idea, which he refuses to even acknowledge. Following this exchange between Chigurh and Carla Jean, the film cuts to the hitman’s exit, but the book does not favor this less ambiguous approach. Instead, after Carla Jean finally admits to understanding Chigurh’s view, he shoots and kills her.

Intriguingly, however, the next scene catches the audience quite off-guard—as Chigurh is unexpectedly injured in a car collision by a vehicle that ran through a red light. Two young kids rush to help the wounded hitman—Chigurh’s bone poking out through his skin—and he offers money in exchange for their shirt: an automatic gesture of kindness for the kids, but which then turns into a dividing argument about how to split their newfound money between them, while Chigurh flees before the police can arrive.

Chigurh’s societal corruption can be clearly evinced yet again through the two kids to whom he bribes for help in his escape. While the two kids approach Chigurh out of compassion to aid a stranger, Chigurh offers the children a hundred dollars for a shirt and to keep quiet about his appearance. As he whisks away using the shirt as a sling, the kids bicker about splitting the money. Like a virus, Chigurh’s actions begin to corrupt these two kids—two kids who were ready to help someone out of the good of their hearts but who soon believe that their efforts deserve compensation, which then evolves into an argument that divides the two friends.

While the film stops there, the book follows Bell’s investigation further into tracking down these two children. Specifically, some time later, he tracks down the boy by the name of David DeMarco, who has been involved in a robbery using Chigurh’s gun stolen after the wreck. Bell invites the boy to share a coffee, and though he attempts to prod him for information, DeMarco refuses to divulge any details that may help the Sheriff identify Chigurh. Later, Bell manages to track down the second boy—DeMarco’s friend—who did not receive any money. And though nervous, he does indeed help the Sheriff with what few details he can remember and his memory of the event. Though not able to offer any significant details, the Sheriff thanks the boy for his help.

The fact that the first boy keeps his word to Chigurh in exchange for the money makes further explicit this theme of corruption. Much like Chigurh, he chooses to honor the bond of his word and the sanctity of the money exchange rather than aiding the law officer. And the second boy, though still visibly scared by the experience and Chigurh’s presence, who did not accept the cash, still speaks to the Sheriff to provide some help against Chigurh—one who has corrupted his former friend into following in his footsteps.

In the aftermath of these events, with no sign of Chigurh reappearing on the Sheriff’s radar, both the novel and film conclude with Bell’s final reflections on his attitude toward his declining country. After a lengthy confession in the book, the reader learns that the Sheriff still bears a great deal of shame for an incident during his war years. Though awarded a bronze star in WWII for his services, the Sheriff had actually deserted his men to die and has carried the regret of his failings to the present day—these shameful failing perhaps the source of his decision to pursue a role as a lawman where he may correct wrongs and govern over evil.

The Sheriff meets with his crippled uncle Ellis—a former lawman as well—where Bell confesses that he feels outmatched. His uncle sighs, and tries to remind Bell that his feelings have been shared by lawmen for far longer than he may recognize: “what you got ain’t nothin’ new, this country’s hard on people…can’t stop what’s comin’…it ain’t all waitin’ on you…that’s vanity.”

Though the scene in the film works to similar poignant effect, this additional information about Bell’s haunted past helps further expose the vulnerable layers that compose this complex officer of the law battling with both his past and future as a Sheriff. Nonetheless, he does indeed hang up his hat—choosing to spend time with his wife rather than fighting against what appears to a worsening country where he does not belong.

Returning to the Yeats’ poem from which the story takes its name, the poem continues:

O sages standing in God’s holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing‐masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

In the story’s final pages, Bell relates two dreams to his wife. In the first, his father gives him some money and he loses it. In the second, he and his father are in:

“older times, and I was on horseback, going through the mountains of the nights, going through this pass in the mountains…it’s cold, there was snow on the ground…he rode past me and kept on goin and never said anything goin’ by, just rode on past…he had his blanket wrapped around him and his head down, when he rode past, I seen he was carrying fire in a horn the way people used to do, and I could see the horn from the light inside of it, about the color of the moon…and in the dream I knew that he was goin’ on ahead, he was fixin’ to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold, and I knew that whenever I got there, he’d be there.

And then I woke up”.

Like any great piece of art, this enigmatic dream has engendered a wide variety of interpretations. However, when considered in relation to the poem from which the title takes its name, the parallels between these two pieces become starkly evident. As the poem addresses this yearning for a haven that offers sanctity from the degenerative nature of the physical world, the protagonist asks the sages that have already arrived within this realm to allow his union with them in this eternal fire. The poem speaks to a being aware of both his past, and deteriorating future, and who seeks some glimpse of immortality through this land of Byzantium—one where the wise sages have already arrived before him and transcended to immortality through a separation from the physical world.

Likewise, Bell’s dream with his father represents his own Byzantium after death. His father, also a former lawman (a wise sage) rides past his son into this immemorial landscape—one in which darkness surrounds them but through which the father carries the fire of a far more ancient tradition. With the cold, dark terrain perhaps representing some death, where his father now resides, this fire of immortality—of an eternal soul—resides within both Bell and his father and waits for the former’s imminent arrival.

Now retired, painfully aware that death is not too far ahead, the thought of his death and legacy weighs heavily on the Sheriff’s mind. This dream of reuniting with his father in some immortal land with the fire of their spirit still blazing amidst an occluding darkness offers Bell some sense of intrigue, possibly hope, until realizing—

That then he woke up.

Though this dream may have given the former Sheriff a perplexing vision of hope, for now, he remains an occupant of Tyrell County, Texas. A world where men like Chigurh continue to roam free and corrupt the lives of all who cross their path. While No Country for Old Men remains an engrossing cat-and-mouse game between these three men—each existing to perpetuate their own definitions of morality—this premise distinguishes itself from so many genre pieces by offering a complex psychological and moral parable in the face of a worsening world.

“What you got ain’t nothin’ new”, Bell’s uncle warns him; and indeed, the story speaks to a universal feeling shared by generations observing what appears to be decline of the next. Still, the arrival of Chigurh—a man embodying principles of immorality that transcend money, drugs, or normal societal codes of good and evil—represents the manifestation of these anxieties. He is a force of a nature—something which cannot be governed and which ultimately challenges the entire idea of upholding the law. Not only can the law not stop Chigurh, but his actions continue to corrupt or destroy all that come across his path. Moreover, as demonstrated by the fate of DeMarco, Chigurh’s choices will continue to plague and warp such values into the future.

Despite such a dire conclusion, the poem from which the title derives its name—and as further intimidated by Bell’s second dream—there lies a silver lining of liberation in looking past the confines of the physical world. The symbolic Byzantium—a realm where man’s spirit has transcended the degradations of both material society and the physical limitations of the body—offers a glimpse into a landscape where not even the unstoppable corruption of men like Chigurh can attempt to worsen the world. Instead, the Byzantium beyond death, which Bell accesses in his dream, occupies a terrain outside the time and space of material consciousness—one in which those that have already arrived continue to carry on the light of tradition against a worsening darkness. Though Bell wakes up from this dream, still imprisoned to the physical world to which he perhaps no longer belongs, he and the reader are given a description of a land where he does indeed belong—one where he, his father, and the men of this tradition have finally transcended those limitations of their former country—and continue to carry the fire, fixing it out there in the dark, and waiting for whomever will join them in the days to come.

Pingback: No Country for Old Men – meatthemoviesblog

Pingback: FRIDAY NOVEMBER 11 2016… | daucktaghscot's aplit blog

EXCELLENT ARTICLE. Nevertheless, not sure that I agree with your assertion that:

“The Texas lawman cannot comprehend the rising violence, because he refuses to believe that a person can only exist in this one regard—to perpetuate and commit acts of violence—and therefore he cannot prevail over this unnamable idea, which he refuses to even acknowledge.”

In the end of the movie, Bell comes to understand the unrestrained intelligent evil of Chigurh and consequently, refuses to call him a “lunatic” when speaking with the El Paso Sheriff.

Roscoe: He is just a goddamn homicidal lunatic, Ed Tom.

Bell: I’m not sure he’s a lunatic.

Roscoe: Well, what would you call him?

Bell: I don’t know. Sometimes I think he’s pretty much a ghost.

Roscoe: He’s real, alright.

Bell: Oh yes.

The violence breaking out around him forces Bell to reexamine his own ability—and willingness—to deal with this new form of criminal brutality. The elderly lawman, product of an informal code of honor that belongs to generations past, comes to doubt whether he is any longer suited to his work. This new era demands an equally brutal response of a kind he is unwilling to muster lest he “put his soul at hazard.”

Have not read the book but watched the movie numerous times. It captivates me each and every time in different ways. Kudos to all associated with this fine film.