“After You’ve Gone”

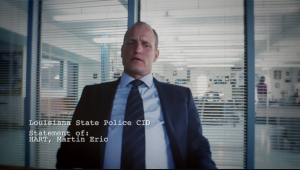

Sharing the beer promised at the conclusion of episode six, Marty and Rust engage in a very awkward reunion at a nearby bar. The two play a subtle game of verbal cat-and-mouse, lobbying occasional jabs at one another, until getting down to brass tacks. Rust has returned from eight years in Alaska to finish the job, and he needs Marty’s help. Though Marty is extremely reluctant to rejoin him, Rust insists that they have a debt to pay in solving this crime (not to mention Marty’s killing of Ledoux that robbed them of potentially crucial evidence). Though still not completely committed, Marty accompanies Rust to his storage locker to continue the discussion…

Arriving at the storage locker, Marty straps himself with a gun—perhaps still suspicious of Papania and Gilbough’s suspicions that Rust is the killer. Upon walking inside, however, Marty quickly comes to understand the truth: that Rust is as committed and obsessed as ever in finding the true killer. Clues, leads, and all forms of evidence adorn every corner of the small shed—a literal manifestation of the locked room that is Rust’s mind.

While absorbing the unnerving display of evidence, Rust further updates Marty on his progress with the case. After following a trail of charges around the Tuttle Wellspring schools, he tracked down a former student/current transvestite—Johnny Joanie. During the interview, Joanie admits that the faculty would induce the children into a “ghost sleep”—where the students would think they would be asleep—but feel awake—and still be unable to move. He further explains that the men would have animal faces, so he felt it had to be a dream. Back in the shed, Rust explains how this cult responsible for the cirmes mixes traditions of courir de Mardi Gras, Santeria, and voudon in their strange rituals accosting women and children. Despite this barrage of evidence, Marty remains convinced…until Rust shows him the tape.

Rust obtained this videotape by robbing Tuttle’s Baton Rouge residence—putting to use his skills as a former B&E man—and also acquiring incriminating photos of a young girl whose eyes have been enshrouded by a cloth. Rust finally plays the videotape for Marty, where the cult leads a young girl into their ceremony. Marty screams and shouts in witnessing the off-screen crimes of pedophilia until Rust finally turns it off. When questioned whether he killed Billy Lee, Rust denies it—believing that it was other men who found out about the robbery and killed Billy Lee before he may be blackmailed. After witnessing the horrors, Marty tacitly agrees to reform their partnership to solve the case.

He then visits Maggie at her new palatial home, where pictures of an older Audrey and Macie are similarly found. He questions her about the Papania/Gilbough interview, and the status of his daughters, and to which she demurs mostly passive answers in reference to Rust. Nonetheless, sharp as ever, she also asks Marty if after all these years gone by, he has only come to say goodbye before finishing whatever it is he has agreed to help Rust finish. Later, Maggie visits Rust at the bar, though he remains similarly reluctant to promise that harm will not come to Marty when finishing the task at hand.

Marty and Rust set up headquarters at the former’s new P.I. offices, where Rust semi-insultingly asks if they need to worry about a lot of people coming in and out, to which Marty hilariously responds: “What do you think, Rust?”. After redecorating the office with much of the evidence found in Rust’s storage unit, the two then bond over their time in the intervening years. A moving montage plays out depicting Marty’s now very lonely life—a failed Match.com relationship, dinners and movies alone—a life much more quiet and removed for the formerly social and motivated family man who instilled so much of his identity vis-a-vis his career. Rust describes a similarly quiet and removed lifestyle—his days filled with tending bar, drinking, and working in isolation. The two share a moment of bonding in equally regretting their career choices: Marty having wanted to be a baseball player or bull rider; Rust, a painter or historian.

The next day, Marty investigates the old police department to retrieve missing persons reports from their archives under the guise of writing a book.* The two are able to track down a Jimmy Ledoux—distant relative to Reggie—at his automotive repair shop. He confesses to know very little of that side of the family which his father described as “too white for white trash”, except confessing that they always shot him with disturbing looks. The reunited detectives are also able to track down a former Tuttle housekeeper—Miss Dolores. She reveals that Sam Tuttle had a number of illegitimate children, and after some prodding from Rust, believes that the scarred man was actually a Tuttle with the surname Childress. She’s then seized by a hypnotizing spell of sorts at the memory, as her voice and speech transforms at the mention of Carcosa.

*(And in a moment of apparent meta-humor, Marty’s fake book is titled “True Crime”—“the genre not the title”, he explains).

Afterward, Marty further tracks down the fact that the Marie Fontenot missing person report “filed in error” was made by Sheriff Ted Childress in ’95—his last name now causing obvious implications as to why it was made in error. Marty also realizes that their former colleague Steve Geraci was the Deputy reporting to Childress. Moreover, they find that Geraci now serves as Sheriff of Vermillion Parish. While Rust is ready to interrogate him with jumper cables, Marty attempts to first reach out to him for a game of golf.

On the course, Marty tries to slyly wedge out information from his former colleague, but the man remains reticent to divulge more information about handling the report to Sheriff Childress. When saying goodbye, Marty can immediately spot that Geraci is lying and calls Rust to “ready those jumper cables”. On a boat not too soon after, Geraci and Marty are enjoying their morning of fishing and beers, when the latter again begins prodding for answers. Geraci finally decides that he has had enough and refuses to say anymore, until Rust finally reveals himself with a handgun—prepared to torture him for answers.

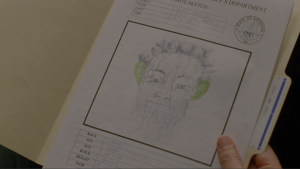

Meanwhile, Papania and Gilbough are found wandering the bayou backwoods in search of the Church described by Rust during his interview. Without any luck, they pull over to ask a man on a lawnmower for directions. The lawnmower man informs them that the Church burned down, and then directs them toward the freeway. The two detectives drive off before the latter has even finished his sentence. Nonetheless, the lawnmower man finally stands to reveal himself to be the same lawnmower man from Episode Three—now with his beard shaved to reveal scars across the bottom of his face.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

REVIEW

With the interviews now gone, and the storyline now more or less rooted in the present, “After You’ve Gone” uses the reunion of the former partners within this penultimate episode to explore the lost history between Rust and Marty while rapidly advancing toward their finally uncovering the case of the Yellow King. Despite their checkered past, the two bond as only they know how—lobbying passive-aggressive insults at one another between important bits of information. Rust has been in Alaska for the past eight years, while Marty professes to have quit his drinking and become a better man. Though the two exchange insults toward one another’s physical appearances against the ravages of time, the two also seem share to share a tacit understanding of finally being led to this point—as though inevitably so. While Marty protests that he would ever help Rust again (“if you were drowning, I’d toss you a barbell”), Rust’s very simple and pointed explanation that Marty owes a debt is enough to convince him to visit Rust’s storage shed.

Following Papania and Gilbough’s accusations that Rust may be the serial killer, Fukanaga uses the reveal of Rust’s shed to indulge in possibilities of these suspicions. Marty even withdraws a gun when entering the shed—only to stumble upon the truth of his former’s partner’s devolution over the years. The production design on this space is superb—giving the impression of a man obsessed by his job and now unhinged by social norms in a manner that seems so far removed from typical portrays of such psychology previously seen on film and television. Moreover, six previous hours of establishing this aspect of Rust’s character only help sell and lay the firm groundwork into the reveal of the shed as a space that serves as a physical embodiment of Rust’s mind–his “Locked Room” to borrow the title from Episode Three.

The intricacies of the shed help disguise the deluge of exposition that covers much of this scene recounting Rust’s retrieval of numerous, vital pieces of evidence. Rust’s breaking and entering into Tuttle’s Baton Rougere residence uses some interesting dissolves to heighten the intrigue of the moment along with his admittance that “I was aware that I might have lost my mind”. As the show has always done so well, despite the extremely dark nature of the story, the hinting as to the horror of what is on that videotape and Marty’s reaction of terror actually works so much better for allowing the viewer to imagine the crimes of these men—crimes so terrible that they compel Marty to work with Rust again despite their torrid past.

But first, Marty must make peace with Maggie. Starting with pictures of Audrey and Macie now grown up: the former on psychiatric meds but also working as an artist; the latter teaching in Chicago for Americorps, Marty seems able to reconcile the fact that this job may end with his death. Maggie, similarly, suspects so, when she asks “Did you come to say goodbye?” And the two are able to share a peaceful goodbye of sorts, after all they’ve been though and accomplished.

Now working within Marty’s quiet P.I. office, the two former partners ask each other a bit more intimately about their lives. These sequences depicting the mens’ lonely lifestyles wrecked with regret and failure are poignant to the point of being heartbreaking. After a string of unsuccessful relationships—online or affairs—Marty has merely resigned to an existence of microwaveable dinners and John Wayne movies alone in his apartment. Rust, meanwhile, remains in a similarly depressing cycle—his entire life now resolved to either bartending, drinking, or obsessive over the case.

There’s an especially moving exchange between the two wherein they reminiscence how neither ever even wanted this career—only to find themselves decades down the line and more than competent at it. Prompting Rust’s line: “Be careful what you get good at”. Nonetheless, it’s also interesting which chosen profession either detective would have liked. Marty, of course, chose the two most traditionally masculine ideals possible: an athlete or a cowboy; while Rust, however, admits that he would have liked to be a painter or historian: “old scenes, new details”. This is interesting in light of the fact of his carrying around his “taxman” book, wherein he illustrates all the details of the scene to provide new context to what others may have missed—somewhat of an amalgamation of these alternatively desired careers.

Marty return to the old office under the guise of writing a book offers what appears to be one of the show’s few moments of meta-humor with Marty insisting: “It’s the genre, not the title” before then investigating the numerous, archived case files. Meanwhile, the two are indeed able to find two key people that allow their progress into the case. The first is Jimmy Ledoux—a relative of Reggie and DeWall. Though embarrassed of Reggie’s name, the man nonetheless further reiterates his abhorrence toward the “Man with the Scars” that seems to unnerve everyone.

It is their second find, however, Miss Dolores—a former Tuttle housekeeper—that provides their most important lead yet. Despite their false excuse for being there, they are able to confirm their suspicions that the man with the scarred face is an illegitimate child of Sam Tuttle—one with the surname of Childress. Her sudden, startled turn and extreme change voice errs dangerously close to hammy, and it’s the one moment of the series that seems to lean on the supernatural unnecessarily and jarringly. Still, her statements that Carcosa is “a wind of invisible voice” holds some resonance for what happens in the finale—wherein the detectives hear Errol’s voice taunting them from within “Carcosa”.

Afterward, sharing another late-night drink, the two probe deeper into the devolution of their lives. Rust (as he has always been so capable of when eliciting confessions) asks Marty again why he quit the force, and Marty finally relents in explaining. After a meth raid, wherein the criminal attempted to microwave a baby, he decided to call it quits—never wanting to see something like that again. The scene is shot with a sense of foreboding dread within those few seconds that—like with the videotape—is never marred by flooding the viewer with the dreaded imagery. Again, it’s the look on Marty’s face—keeping the corpse out of focus—that makes the visual all the more powerful. And afterward, Rust’s actual confession as to why he had to return from Louisiana to finish the job turns out to be a more sorrowful reason than even Marty’s. As Rust explains: “This [was] something I had to see to—before getting’ on with something else…My life’s been a circle of violence and degradation…I’m ready to tie it off”. The idea that Rust is ready to commit suicide after finishing the task at hand is at once both heartbreaking and a perfect set-up for his fate within the finale.

And finally, the man with the scarred face—almost comically revealed through the arrogance of Papania and Gilbough—at last arrives within this penultimate episode. Accompanied by eerie toybox music, bathed in the golden light of a dying sunset, Errol Childress is revealed to be the lawnmower man that Rust first met in Episode Three outside the Light of the Way Academy. Removing the who-done-it at this point in time turns out to be an incredibly wise move on the part of Pizzolatto, for as the series has done excellently throughout, it both eschews traditional expectations of the crime genre in television and allows a stronger focus on character.

Characters whose fates will all finally converge in the next and final episode.