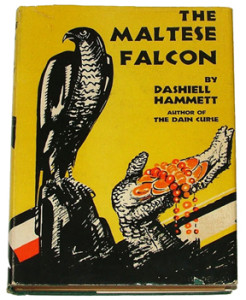

With Dashiell Hammett’s novel serving as a literary prototype for the hard-boiled detective genre, and the film adaptation arguably considered a model—if not the very first—of the film noir genre, both versions of The Maltese Falcon deserve examination for their consideration and influence within their respective mediums. Starring Private Eye Sam Spade at the center of this byzantine narrative, the almost comically convoluted plot revolves around the eponymous statuette of The Maltese Falcon—a bejeweled figure worth a significant sum of money that fuels the motives of each character. More importantly, the Falcon functions as an archetypal MacGuffin—a plot device term famously popularized by Hitchcock—as an object whose inherent nature bears little importance, so much as it catalyzes the characters’ pursuit of this object to reveal their true nature.

Nonetheless, as in so many of the film noirs to come, the story begins with a mysterious woman asking for help. The woman—Brigid O’Shaughnessy—enters the investigate offices of Archer & Spade for their assistance in apparently tracking down her sister. Though the two are suspicious of her story, Archer trails the man in question—only to be later shot dead. With the police now fingering Spade as a possible suspect, he begins his journey into both proving his innocence and avenging his partner’s death.

But first, he must contend with the peculiar character of Joe Cairo (Peter Lorre). While the book’s descriptions make the character’s homoerotic undertones undisguisably clear, the film must hint much more subtly toward such controversial character ideas for a film produced in 1941. Instead, Peter Lorre’s performance of Joe Cairo emphasizes such affects through his high-pitched voice, extremely polished attire, and scented handkerchief. That aside, Cairo first introduces information regarding the bird while searching Spade at gunpoint. Though Sam outmaneuvers him, he soon realizes that he is being trailed by a companion of Cairo named Willet—commonly referred to as the kid in the book—who doggedly trails the private eye throughout San Francisco in his search to reconnect with Brigid and determine her connection between his partner’s death and this strange statue of the Maltese Falcon.

Eventually, Spade locates the looming figure operating behind the scenes of both Brigid and Cairo in the form of “The Fat Man” aka Gutman. Played to marvelous, memorable effect by Sydney Greenstreet, the perpetually jovial crime figure attempts to manipulate Spade in finding the valuable Falcon. As can be found in similar, heavily-plotted noirs of the time, the narrative from this point forward mostly allows for a series of tense dialogue exchanges, double-crossings, and a climactic confrontation for all parties in which their object of desire—The Falcon—serves to illuminate the true intentions of each character and challenge those aspects of their personality formerly considered resolute.

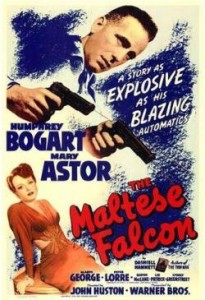

Besides these genre precedents, the film also helped initiate the careers of both director John Huston and star Humphrey Bogart into those iconic roles which would later cement their legacies. Having collaborated with Bogart as a writer on the early heist film High Sierra (1941), where the young Bogie owned his first true staring role as the leader of the heist, Huston and Bogart would use the successful reception of this first partnership to ascend both their careers in The Maltese Falcon. After the critical and box office success of this picture, Huston would pursue similar movies that would define his career, mostly in the crime genre; specifically: The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Key Largo, and The Asphalt Jungle. Meanwhile, Bogart would grow into an actor of legend just a year later when starring in the most famous film of his career: Casablanca.

Though two previous, failed adaptations of Hammett’s novel had already come to fruition, Huston managed to convince Warner Brothers into financing another by meticulously mapping out each shot beforehand in detailed storyboards and keeping the budget down to $300,000 on an eight-week-schedule. Perhaps more importantly, he also remained extremely faithful to the source material—reducing the already lean narrative of the novel into an almost word-for-word transformation from prose to picture.

Still, the single filmmaking aspect most worthy of praise that exalted the picture into a detective mystery far more compelling than its predecessors can be pinpointed to the cinematography. Roger Ebert and others have argued that cinematographer Arthur Edeson’s work deserves praise on par with that of Welles and Gregg Toland in Citizen Kane for its use of deep-focus, long takes, and low-angle shots. These low-angles are noteworthy for their inclusion of ceilings within interior rooms—a major achievement for the field since lighting and equipment were normally kept above this region of the frame to hide equipment. While also praiseworthy for their invention in this regard, these shots also work to thematic effect in visually enhancing many ideas about character. Most notably, these are utilized in shots of Sydney Greenstreet’s Mr. G, wherein the massive man of wealth and influence is continually framed from low-angle shots that emphasize his power and domineering influence upon the frame.

Likewise, he and Edeson employ deep focus shots that ensure each detail in the foreground and background act in unison to highlight deeper thematic ideas—ensuring many long dialogue scenes are able to both convey necessary plot exposition and retain the viewer’s attention from a visual standpoint. Moreover, the use of a long take in a nearly seven-minute-long shot between Spade and Gutman deserves exceptional praise. Though the take does not call attention to itself in the manner that has made so many other long takes famous, the unbroken shot observes Gutman slowly waiting for Spade to pass out from his drugged drink. The viewer wallows in both the tension and patience of the scene, and Huston wisely never interrupts the shot to pander down to audiences as to the why this scene deserves to play out for such an extended time. Though this exact parallel between Toland and Edeson may be a bit of a stretch, the cinematography on display still deserves its reputable acclaim.

Still, though the film’s technical achievements are worthy of all the esteemed praise accumulated over the decades, the film’s genre and character precedents remain its most relevant legacy. Bogart inhabits the smug, cold, yet oddly charismatic character of Spade with confident swagger and delineates a portrait of the hardened detective that would inhabit the noir genre to the point of cliché. What separates Spade from the imitators, however, can be found in the stirring sense of pathos—one which will soon be starkly illuminated in the climax.

Like the novel, the final scene plays out as one long dialogue scene that begins as a negotiation and concludes in a cold arrest. The nearly twenty-minute long scene plays out almost identically to that of the novel, though the book includes a scene of Spade strip-searching O’Shaughnessy in an act of humiliation that truly reveals Spade’s hard heart—foreshadowing the dark aspect of this character to be crystallized within the climax.

After the Falcon has been revealed as an imitation, and the original “Fall Guy” of the Kid has escaped, Gutman and Spade mutually agree to depart with no harm to the other (though Spade manages to take a few hundred dollars from him “for his troubles”). Left alone with his love interest O’Shaughnessy, the woman who originally entangled Spade within the affairs of the Falcon, she appeals to Spade no longer as an ally or client—but as a lover. She raises questions of their relationship, of love, but Spade’s true nature finally reveals itself when he bluntly explains that he will be handing her over to the police. Though apparent true tears emerge from the woman’s eyes, begging him for mercy and for him to escape with her for a new life, Sam can only explain in his famous last lines:

“When a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it…I hope they don’t hang you, precious, by that sweet neck…The chances are you’ll get off with life. That means if you’re a good girl, you’ll be out in 20 years. I’ll be waiting for you. If they hang you, I’ll always remember you.”

Despite Sam’s brutal message and Brigid’s look of absolute horror, the speech gives the best indication yet into Spade’s character and what separates this species of investigator from the others: a code.

While Brigid may have actually loved Sam, her ambiguous nature left little in the way for a man like Sam to love her back. Even though he may not have even liked Archer (and was holding an affair with his wife, as well), and though he may have liked Brigid in some other circumstance, his code dictates that he has a certain duty to fulfill—one that he has accomplished by the end of the story—and one that, for better or worse, leaves him back where he began.

The one major, final difference between the book and movie lies in the film’s famous last line. After a cop asks Spade as to what exactly the Maltese Falcon is, he replies: “The stuff that dreams are made of”. Though reports vary in crediting this line to either Bogart or Huston, the line works as a variation of dialogue from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “We are such stuff / As dreams are made on, and our little life / Is rounded with a sleep.” The line does not need much analysis in the way of deciphering its symbolic significance in relation to what the Falcon has represented: a device that fueled the dreams for those seeking greater glories, riches, and a happier life…only to come away with nothing but an imitation.

Although the film is almost a word-for-word adaptation of a novel, it does leave out one chapter of significance that highlights this idea of chasing something better only to return to a similar life as that which came before. In the chapter titled “Flitcraft”, Spade relates the story of a case from early in his career, which involved a man named Charles Flitcraft. Spade had been assigned to track down this Charles Flitcraft—a successful businessman from Tacoma—who had seemingly abandoned his family. Following his private investigation, Spade discovers that Flitcraft was nearly killed by a falling beam from a construction site, and though the nearly fatal beam just missed him to spare his life, the businessman remained deeply shaken from the experience. As a result, he decided to leave this life behind in search of a new one. His new life, however, came to find Flitcraft as a man in charge of a new business, with a new wife, not far from his original town of Tacoma—clearly unaware how closely his new life resembled the old one.

The point of Flitcraft’s story—and one that makes Spade’s own ending with the Falcon all the more haunting—relates to the this theme of a man being unable to change his true nature, arguably due to the code which so defines Spade’s character. With the Falcon acting as The MacGuffin in this case—a thing that dreams are made of, whatever that may—each character comes to chase this idol of hope only to return to that original life from which they started their doomed journey. Cairo, Gutman, and Willet return to their worldwide search of the actual Falcon, Brigid remains a woman in fear for her life (now under a pending death penalty), and Spade returns back to his office—ready for the next case.

Now having experienced an episode in the career of Sam Spade, the viewer can better understand and contextualize the cynical weariness that has turned this private investigator into a shell of a human being. A man who understands the importance of a code above all else, and who’s able to recognize the futility of chasing a better life that will only return the pursuer back to a life not too dissimilar from the start. Ultimately, Spade recognizes that all these things under the umbrella of “stuff that dreams are made of” represented by the Falcon – a new life, a better woman, untold riches, the solving of a case—are only ever just that for men of a certain nature: ephemeral goals capable of casting the illusion of change, only to crumble over time when a man must return to his true nature and follow the law of his own code.

While the weary, detached detective would become a defining element of noir in the ensuing years, Spade’s sad fate as a man forced to return to a lonely lifestyle defined by a rigid code serves as a significant example of how this noir archetypes and his function within the larger narrative recontextualizes such ideas with profound thematic meaning that relates to dark ideas of both man and the mirage of dreams. As downbeat as such ideas may be, they represent the subversive tropes that came to define the film noir and detective genres at large—themes and characters represented in classic, captivating fashion as best found in the case of Sam Spade and The Maltese Falcon.