Like last year’s equally commendable Gravity, Ridley Scott’s The Martian pits a lone protagonist against the vast abyss of space to examine the phenomenal capabilities—and crippling weaknesses—of a determined human mind as can often best be explored through the sci-fi genre. Though the two films are remarkably different in tone, both feature a single character forced to battle against both the unforgiving elements of outer space and the interior war within their mind. While Cuaron’s Gravity infuses the terror of this struggle through an atmosphere of dread, Ridley Scott’s The Martian relies much more heavily on humor to highlight its own themes of man’s survival through critical thinking and collective effort.

Gravity

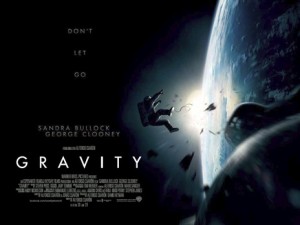

Opening with a title card that warns: “Life in space is impossible”, Gravity begins with Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and her veteran colleague Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) repairing the Hubble Space Telescope. In this brief scene, Cuaron allows the suffocating silence of space to be glimpsed in between their intercom dialogue, while also foreshadowing Stone’s careful—though visibly anxious—maneuverings to avert any fatal mistakes. Nonetheless, falling debris from a destroyed Russian satellite leaves the rest of their crew dead—stranding Stone and Kowalski alone in the void.

While this opening sequence serves both to imbue a sense of awe in its deliberately paced display of distant Earth and the limitless reaches of surrounding space, the light dialogue between Stone and Kowalski offers some impression into her horribly anxious disposition contrasted against Kowalski’s calm confidence. As the chaos of the debris steadily rises in tandem with the subtle score, Stone remains transfixed on her task—unable to free herself from her current, “safe” job. Even when Kowalski gives her a direct order, she struggles to separate herself from the comfort of the work in order to pivot for safety. Repeatedly, this theme will come to define Stone’s psyche—as a woman unable to overcome her current predicament and push her way forward.

Moreover, Cuaron frequently employs long shots to sustain the immediacy of the moment and situate the viewer within the characters’ POV. While the film’s technical achievements have already been discussed at length (and deservingly so), the emotional and thematic importance is never sacrificed in favor of these spectacular displays. The viewer experiences the terrifying experience of hurtling through blackness, reeling farther and farther back from Earth, while these incredible visuals only serve to enhance the experiencer rather than distract for the sake of spectacle.

In refusing to cut (or at least employ “invisible cuts” to maintain the illusion of seamlessness), Cuaron never allows a reprieve from the stultifying and worsening conditions of the hostile environment. The subtle, effective score further cues these emotions—providing an additional layer to the chaotic and disorienting dialogue. Most importantly, it illustrates both the urgency and dire consequences of the premise—making clear that the cruel landscape of space demands for the astronaut to either die or adapt—a theme soon to become the core challenge of Stone’s character.

As Stone tumbles through space completely adrift against the interminable blackness, Kowalski manages to save her using his MMU (manned-maneuvering unit) and the two return to find the rest of their shuttle crew dead. Left with no other option, the duo press forward for the International Space Station. In the interim, Stone moseys forward with Kowalski, who does his best to alleviate her anxiety through small talk. In this dialogue, Stone sheds light on the incident that has so defined her current disposition, when she explains that her daughter died in a random tragedy after hitting her head during a schoolyard game of tag. She details further that when receiving the news, she was driving and listening to the radio, then sadly mutters, “since then, that’s what I do”. This behavior—of being trapped by the past and unable to move forward—has turned Stone into something that resembles her namesake, an immovable block rather than a human being able to adapt and thrive.

Still, after arriving at the ISS, they find that only one of the two Soyuz modules remains. Worse, the other module’s parachute has already been deployed. Kowalski still figures that they may still be able to reach the Chinese Space Station—The Tiagong—to use one of their modules. However, the deployed parachute chords entangle the two astronauts—endangering both their lives. And in order to save her life, Kowalsi detaches the chord to sacrifice his own for Stone’s.

After another distressing sequence of POV shots when Stone must escape from a fire outbreak aboard the ISS, she finds herself within the Soyuz module—only to discover that the fuel has been depleted. With the relentless forward momentum of the plot so far—excepting Stone and Kowalski’s sojourn to the ISS for crucial character building moments—the pacing decelerates to allow the audience to absorb the magnitude of Stone’s utter hopelessness and producing perhaps its most poignant and emotional scene.

After attempting radio communication with Earth, she instead finds herself conversing with an Eskimo fisherman. Having finally found another human connection, the other side is not only not Mission Control, but a random fisherman incapable of communicating back with her, and there’s recognition that her favorite activity since the death of her daughter—just listening to the radio—has now become her last connection to humanity before surrendering to death. She resorts to imitating the howls of a dog heard in the Alaskan background; and then, only through these howls, can she communicate with her fellow man. With small, uncontrollable tears, she lets loose pitiful howls in finding someone else to speak to—shedding tears in communicating with a fellow man; no longer as an American with an Alaskan, or a woman with a man, or an astronaut with someone back on Earth—but as two animals sharing the experience of being alive through this howling of the soul.

Believing that this represented her best hope at returning home, Stone accepts her fate—begging to this listener that can’t understand her with a final testimonial that reveals the overwhelming fear consuming her spirit: “I know I’m gonna die, I’m gonna die today…but I’m still scared, I’m really scared…No one will mourn for me, no one will pray for my soul…”

Bullock’s performance remains steadfast and subtle, never opting to turn this emotionally rendering moment “loud” or melodramatically alter what has been defined as her character’s timid behavior. Instead, she applies restraint and allows these powerful emotions to translate the existential desolation of the situation—making tangible the enormity of her suffering within this small island of safety and the looming certainty of death. Resigned to her fate, Stone deactivates the cabin’s oxygen supply to commit suicide—the lullaby of her Inuit friend Aningaaq drifting her toward unconsciousness—when the film suddenly departs from the stark reality that it has so far effectively hypnotized the viewer into believing and re-introduces the specter of Clooney’s Matt Kowalski.

Despite the obvious hallucinogenic/fantasy aspect of this device, his pep talk to Stone makes explicit the film’s major theme. While the fact that the dialogue so bluntly states its message would be irksome in most filmmakers’ hands, Cuaron has so successfully imbued the subtle nature of Stone’s incredibly timid and reserved character up to this point—a character quality often very difficult to translate to the screen with nuace—that allows these tender emotions to be so successfully evoked. As has been repeatedly demonstrated, Stone is a woman incapable of moving forward—a woman more willing to resign to emotional paralysis than risk the potential for pain.

Kowalski addresses this attitude in saying:

Do you wanna go back or do you wanna stay here? I get it, it’s nice here…just close your eyes and tune out everyone…it’s safe…there’s no one up here who can hurt you…what’s the point of going on? What’s the point of living….your kid died, it doesn’t get any rougher than that…but it’s still a matter of what you do now…and if you decide to go, then you gotta get on with it…gotta plant both your feet on the ground and start livin’ life…”

Kowalski speech motives a newfound fire within her, and she follows his instructions to rig the Soyuz’s jets to connect with the Tiangong and initiate her return journey home. Avoiding the subsequent obstacles that then arise, she enters the capsule and begins her deployment back to Earth. Though a fire within the capsule threatens her safety, she survives the harsh landing into a lake, where she now must swim against the drowning waters and ascend to the surface.

Having struggled so much in the upper echelons of space, Stone’s fight to swim back up to land now deserves special praise. Where so many filmmakers would be content with an easy victory upon her crashing landing to earth, Cuaron pushes the character further and deprives Stone of an easy ending—just as she has finally found her way back home. Yet, Stone does indeed manage to survive—and in a sequence that echoes with symbolism toward the evolution of life itself—Stone reemerges from the waters, rises from the dirt, and takes her first slow, shaky steps back upon planet Earth.

As the story of a single person’s survival within the hostile arena of space, Gravity can often be an unsettling, though ultimately, very triumphant experience. The story positions the darker aspects of a person’s ability to cope with trauma and rise above those shackling flaws of their past to the forefront, and the cinematic techniques on display further immerse the viewer in the terrifying dread of such a premise: specifically, POV shots hurtling through space, the unnerving quiet of the surrounding void, and the utter loneliness of the deathly atmosphere. Cuaron conveys all of these deeper existential questions of a character’s determination through a tone that conjures the dread of such a harrowing experience and being ability to surmount such fear through the exertion of courage and continuing to advance forward.

The Martian

Meanwhile, The Martian shares a very broad narrative overlap involving the survival of a lone protagonist in space. In this case, however, that hostile territory is Mars; and the protagonist, astronaut Mark Watney. Unlike Gravity, the filmmakers follow a wildly different route in portraying the experience of a human’s fight for survival on a planet hostile to human life—employing humor, a more light-hearted tone, and an ensemble of characters to emphasize its themes of survival through critical thinking, persistence, and collective effort toward a common goal.

After an unexpected storm causes the crew of Ares III to abandon Mars, astronaut Mark Watney finds himself isolated upon the planet due to the damage done to his biometer that designated him as a dead man. When awakening to find himself alive, however, Mark trudges back to the Hab—the habitable human settlement established upon the planet—and, after a restless night of internal questioning, declares that this is not the planet where he will die.

Applying both his knowledge as a botanist and his unwavering willpower, Mark uses the marriage of his science and intellectual prowess to overcome the multitude of seemingly impossible obstacles that appear determined to destroy him. He creates water, food, heat (albeit with a potentially fatal radioactive plutonium) and—even in being responsible for numerous mistakes in the process—still presses forward until he finds success. Throughout these trials, Watney maintains a video blog both for prosperity’s sake and to sustain his moral in the midst of such isolation.

While Gravity’s sense of urgency continually keeps the forward momentum compelling and imbued with a feeling of immediate danger, The Martian must contend with a drastically different narrative timeline that creates an unusual storytelling challenge: building a sense of urgency while also allowing the audience inside Mark’s head. As the monotony of his day-to-day activities would grow tiresome or confusing without any explanation, the device of the video blogs helps alleviate these narrative problems.

Meanwhile, back on Earth, NASA has realized that Watney is actually still alive and begin their own quest in figuring out how to bring their man back home. Because Watney’s activities transpire over such an extended period of time, the story wisely intercuts between those on Earth attempting to bring him back and Watney’s own problems on Mars in order to intensify the struggle and give a glimpse toward the literally cosmic scope of this problem.

As NASA determines the various financial, moral, and practical difficulties in solving that problem, Watney must contend with those battles and victories in the short-term that will allow his long-term survival. The filmmakers construct these sequences as mini-movies of their own right—allowing a constant sense of triumphs and defeats that disguise the longevity of the story’s timeline. Whether it’s finding food, creating water—all seemingly impossible tasks—each problem is constructed around sequences of beginnings, middles, and ends that allow for Watney’s creative solutions to achieve a short victory before returning to yet another seemingly impossible choice to be encountered by NASA.

After Mark manages to reboot the original Pathfinder probe and establish communication with NASA, however, a new dynamic between Earth and the Martian begins to form. More interestingly, the arrival of communication—through the use of the hexadecimal alphabet—demonstrates how important language stands for human survival. Whereas Gravity focused more on this single woman’s psychological journey traversing through space, The Martian distinguishes itself by relying more on a network of people to ensure his successful survival back home—highlighting how important collective effort toward this goal can be and how communication may be the ultimate tool for accomplishing this task.

Most importantly, with the idea of communicating being such an essential feature of this film, comedy and humor become a much more prominent tonal element woven into the fabric of the story. While compelling and vital for the examination of Stone’s character, Gravity maintains a grim, dour tone throughout—appropriate for its specific story—in order to diffuse the sense of hopelessness permeated within Stone’s psyche upon the viewer.

The Martian that is Mark Watney is a very different astronaut. Determined to overcome his dismal situation, Mark maintains a relentlessly optimistic personality and tackles each individual problem in careful, measured steps while narrating his decisions through video blogs that sustain his positivity despite the utter lack of human connection around him over the prolonged time period. Though Cuaron routinely employs unbroken takes or extended sequences that further transport the viewer within the suspense and danger of Gravity’s premise, The Martian opts for a more relaxed, light-beat tone to keep the audience engaged. From rapid time cuts of Mark growing his new potatoes, to montages set to disco music, to comic cuts of Mark complaining about said disco music, this humorous tone endures throughout—replicating the tone of Mark’s indomitable spirit upon the audience to experience this harrowing journey with a feeling that his quality of life need not be completely destroyed.

Still, the fun does not last for long: as both Mark and NASA each encounter significant setbacks. On Mars, Mark’s HAB malfunctions due to a human fault of his own that renders his crops unusable and sunders the entryway—forcing him to protect himself from the elements with a noisy, insecure swath of tarp. Simultaneously, NASA initiates a space probe launch designed to aid him with supplies until the arrival of the Ares IV—only for the probe to disintegrate due to the director’s decision to forego safety inspects in favor of helping out Mark as soon as possible.

After beginning afresh with his new crops, the first hint of darker psychological anxiety creeps its way into the previously positive tone. While Mark rations out his food supply, intently listening for any possible damage to his tarp acting as his shield against the brutal Martian weather, he repeatedly tries to hide the anxiety threatening to paralyze him. Though only a brief moment, the scene shows Mark flinching every time the tarp flaps against the severe winds just outside and demonstrates how perilous the slightest tear could endanger his life. As he calculates his potato rations, this glimpse into Mark’s anxieties just beneath the surface provides an interesting change in tone that reminds the viewer just how truly dangerous and subjected to the mercy of elements outside his control Mark’s life currently remains.

Faced with few options at this point, NASA receives a boon from the CNSA in the form of a classified booster that they are willing to lend to the Americans. At the same time, Donald Glover’s Rich Purnell figures an alternative method for rescue—by using the booster to resupply the Ares III and allow the astronauts to return to Mars, recover Mark, then return back to Earth.

Set to Bowie’s “Starman”, another montage helps disguise the extended period of months that these machinations will necessitate, as Mark also needs to begin his own long journey across Mars to reach the site of the future ARES IV launch. By the conclusion of this stretch before the climax, the stakes have been significantly raised and the passage of time shows some deterioration in Mark’s previously unwavering mental state. Mark now sports a grizzled beard, various sores across his skin, has lost a significant amount of weight, and his teeth have begun to rot. Nonetheless, he retains his sense of humor throughout the endeavor—now calling himself a space pirate—though his humor appears to cause NASA more trepidation this time around than at the start.

As the crew initiates their rescue, Scott allows for a touching moment that exposes these cracks in Mark’s previously unbreakable composition. When the crew begins the countdown, and Mark knows that he’s finally about to engage in the most important few minutes of his life to either die or finally leave behind the isolating land of Mars, he breaks down and sheds tears that both release his repressed anguish and celebrate the triumph of having survived this long upon the hostile planet.

Finally, the rescue begins. At each step of the turn, some unforeseen variable seems to destined to doom the endeavor—whether it’s the weight of the launch vehicle, the distance between Commander Lewis and Mark that prompts him to poke a hole in his suit to fly through space (not unlike Stone’s use of the fire extinguisher), to the dozens of other unforeseen factors that threatened to endanger all of their actions. Thankfully, Mark reunites with his crew and the climax swells with complete triumph and relief. The film wisely wastes no time following their rescue and cuts to the eponymous Martian now back on Earth—teaching potential astronaut candidates about the power of facing your fears and solving each problem in order to survive.

Watney proved him capable of conquering every danger wrought both by the Martian planet and his own mental anxieties. While his physical survival necessitated his application of science and indomitable fortitude to overcome these obstacles, The Martian also emphasizes the importance of collective effort toward the goal of bringing him back home. But most intriguingly, the film’s command of tone—balancing unexpected humor in the midst of such a dire situation—helps instill a similar sense of communal experience for the audience that remains such a fundamental component of the film’s story and theme.

Though very broadly similar films in their sharing of a single protagonist in space struggling to survive and return to Earth, both Gravity and the Martian use the sci-fi genre to address a comparable message about man’s resiliency in the face of a seemingly insurmountable situation. In Cuaron’s Gravity, the story focuses on the fight of its main protagonist and her psychological battle to defeat the depression within her that has arrested those capabilities that will allow for her survival. Moreover, Cuaron employs point-of-view shots, subtle atmospheric score, and an often-dire tone that situates the viewer into both the urgency and terror of the premise—framing the individual as the central story to evoke its themes of progress, triumph, and human ingenuity.

The Martian, however, while also focusing on a sole individual confronting the vast difficulties of both outer space and his inner potential for achieving this feat, also broadens its exploration of this theme to incorporate ideas of cooperation and collective effort in spite of such an impossible outcome. In both cases, the filmmakers have crafted an exceptional, distinguished story that celebrates the remarkable triumphs of the human mind: whether through a tone of dread that then illuminates the capabilities of the human spirit, or how the persistence and positivity of a single man stuck on Mars can inspire those on Earth—both films examine the enduring elements of human nature as best explored through the powerful potential of the sci-fi genre.