Within the wide spectrum of the Western subgenre that is the Spaghetti Western, the names of two directors—Sergio Leone and Sergio Corbucci—tower over their contemporaries for a filmography largely responsible for reshaping much of the genre’s modern iconography; while also, and perhaps more importantly, of imbuing the genre with ideas of moral ambiguity and thought-provoking character ethics that clashed against those previous conventions of their American genre peers.

Unsurprisingly, the best demonstration of the directors’ distinct differences, and the profound creative prowess possessed by both Sergios, can be found in those two films that have come to be regarded as their masterpieces and which were released in that same year of 1968. Namely, Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West and Sergio Corbucci’s The Great Silence. Though the two films share the bond of belonging to the Spaghetti Western, the two films take a wildly different approach toward their conception of the West and those staples of the genre that they seek to either elevate or deconstruct. In this sense, Once Upon a Time in the West serves as the model of the “ultimate” Western, while The Great Silence can be viewed, comparatively, as an “anti-Western”.

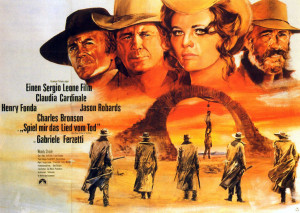

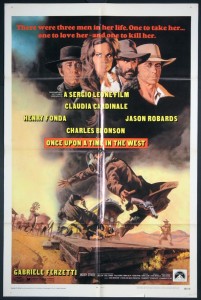

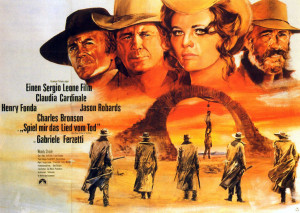

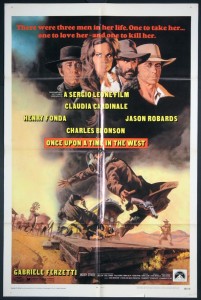

Having now innovated and elevated the Spaghetti Western genre to global heights through his Dollars Trilogy with leading man Clint Eastwood, Sergio Leone had intended the focus of his next film to transition toward a different genre (the gangster film) in what would eventually evolve into Once Upon a Time in America. However, due to the popularity of the Western and attracted by the chance to work with his favorite actor—Henry Fonda—Leone once again returned to the roots of his success. Working with screenwriters (and famed filmmakers of their own right) Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento, the trio worked together to absorb all the familiar tropes, plots, and stock character types normally found in the typical take on the genre (The Searchers, Comancheros, High Noon) then synthesized these various tropes and traditions to compose something that reflected and honored their predecessors—but one that also sought to challenge their core and seek some sense of significance in the pursuit of the genre’s conclusion.

Once Upon A Time in the West chronicles two storylines running parallel to one another and intersecting through the film’s villain—Frank. The first story concerns the quest of the “protagonist”—Harmonica (Charles Bronson)—a mostly mute gunslinger who instead plays his eponymous harmonica when confronted by questions. Harmonica has arrived in the fictional town of Sweetwater in the hopes of hunting down the aforementioned Frank and seeking vengeance—for reasons that will be slowly revealed.

The second storyline concerns the construction of a railroad upon the McBain Property. This tract of land becomes the source of central conflict after the McBain Family dies in a massacre under Frank’s gun, who has been hired by the railroad tycoon Morton—the latter hoping that the removal of the McBain Family will ensure his plans for the railroad will continue unobstructed. However, it is revealed that the McBain patriarch took a wife in secret just before this massacre—engaging himself to a former prostitute now named Jill McBain(Claudia Cardinale), who has now arrived an inheritor to this territory sought after by many mean men. However, she finds help in the form of Cheyenne (Jason Robards)—a bandit leader framed by Frank but who has come to reclaim his name. This unlikely trio—the widow McBain, bandit Cheyenne, and mysterious gunman Harmonica—eventually find their individual pursuits overlapping in order to stop the tycoon and Frank from continuing their path of destruction.

From almost the first frame, the film makes clear its intentions to both honor and subvert those traditions of its genre. The remarkable, nearly ten-minute-long opening set-piece of three men awaiting Harmonica plays clear tribute to that same scene in High Noon, although this features the trio of villains awaiting the protagonist, rather than the villain. Moreover, Leone plays the scene in something akin to real-time, utilizing the creaking of the windmill, the buzz of a fly, and the whines of wood to create an atmosphere of dread to impressive and suspenseful effect. This opening scene announces in clear, cinematic flair as to the heightened level of filmmaking on display and immediately demands that the audience prepare for this epic story about to unfold over the forthcoming three hours.

Leone quickly transitions to another set-piece—the massacre of the McBain Family—where again, the filmmaker takes full advantage of any possible diegetic noises (the chirping cicadas, flapping of birds, rustling bushes) to weave a tense, powerful scene. Moreover, the arrival of Frank and his killing of the child again announces—now in a one-two punch following this opening scene—how Leone intends to recall those memorable conventions of the genre (casting Fonda, the family farm) while also distilling a more uncomfortable, solemn feeling of morality that will entangle much of the remaining narrative.

While the Dollars Trilogy featured a more heightened level of reality, one much more firmly rooted in a sense of adventure that employed Western iconography and conventions to sensationalize these effects, Once Upon a Time in the West saturates itself with this somber feeling throughout its themes, characters, and story. (However, this is not to say the film is humorless. It features some of the best one-liners in Leone’s filmography: “How can you trust a man who wears both a belt and suspenders? The man can’t even trust his own pants.”) Still, Once Upon a Time in the West instead represents a film that embraces its heritage while also contemplating the conclusion of its demise.

Working with longtime collaborator Ennio Morricone, Leone replaces the mood of thrill and excitement that so preoccupied the Dollars Trilogy with a feeling closer to operatic tragedy. Though Leone has always had a penchant for reframing the Western in this these grander aesthetics, Once Upon A Time in the West represents the acme of his filmmaking purview—one that uses this marriage of his theatrically trained eye, his knowledge of film history, and his goal of employing both in the service of creating his concluding Western masterpiece. Though the various, breathtaking set-pieces are indicative of this accomplishment—from the aforementioned McBain Family Massacre, to the opening shootout, to the sweeping view of Sweetwater on display with the arrival of Jill McBain—the final confrontation between Harmonica and Frank may serve as the ultimate manifestation of Leone’s command of cinematic craft.

In creating Frank as a villain far more morally complicated and with far greater depth than with any seen in the Dollars Trilogy (or most American Westerns), Leone complicates the traditional trajectory of the showdown with the protagonist. While Harmonica’s backstory has been slowly dolled out in tantalizing, blurred glimpses that hint toward some terrible tragedy of his past, the climax of their long-awaited battle plays out with far greater pathos than those former (still masterful) shootouts of Leone’s filmography.

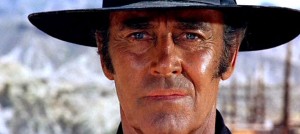

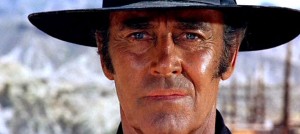

Starting with Frank, Leone introduces this man as an undisguisable, immoral villain. After the tension-filled opening of the McBain Massacre, the icy-blue eyed Henry Fonda slowly reveals himself with the smoking gun and aimed at the youngest McBain boy—whom he murders in cold blood after one of his fellow brigands dares utter his name. Despite this cold opening, Frank is next introduced as a hired gun to the railroad tycoon—a crippled businessman named Morton. While Frank clearly embodies the role of the black-hatted gunman from the opening, Morton also represents a new form of evil, one much more insidious, to soon haunt the American plains with a different form of dominance. In this matter, Morton reminds Frank:

“There are many things you’ll never understand [he pulls out a wad of cash to explain]…This is one of them. You see, Frank, there are many kind of weapons. And the only one that can stop that [the gun] is this.”

This simple truth from a crippled man appears to haunt this former figure of evil as to his remaining place and identity in the changing American frontier—seeming to become a point of preoccupation for him in trying to understand how to sway power in his favor when a fast finger on the trigger was formerly applied as the most obvious answer.

Later, Morton manages to bribe Frank’s henchman into killing him—a move that is countered by Harmonica’s helping hunt down his traitorous companions. Despite Jill’s protests that Harmonica “saved his life”, Harmonica clarifies the difference between “saving” a man’s life—and not allowing others to take Frank’s death from him. At this point in the film, the two gunmen have engaged in a coy dance with one another. Whenever Frank questions Harmonica’s identity, the latter will only answer in the name of dead men—men whose lives have been cut short by Frank’s gun. And after Harmonica’s help in avoiding a bullet from those former fellows bribed away from him, Frank knows that the time has finally come to confront his foe. Although Harmonica often replies in smartass, one-word answers, his dialogue with Frank just before their final confrontation could not better sum up these themes that have been brimming beneath the narrative’s surface:

Frank: Morton once told me I could never be like him. Now I understand why. Wouldn’t have bothered him, knowing you were around somewhere alive.

Harmonica: So, you found out you’re not a businessman after all.

Frank: Just a man.

Harmonica: …An Ancient Race…Other Mortons will be along, and they’ll kill it off.

Frank: The future don’t matter to us. Nothing matters now—not the land, not the money, not the woman…I came here to see you. ‘Cause I know that now, you’ll tell me what you’re after.

Harmonica: … Only at the point of dyin’.

As Harmonica has pointed out, though on opposite sides of the gun, he and Frank both belong to a different race than the type that men like Morton that will soon invade and dominate the frontier. This is a West owned by the men of money and means of power that exist outside the violence of a gun. Moreover, though this showdown works on a scale just as operatic and beautifully composed as that breathtaking final standoff in the graveyard found at the climax of The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, Leone also crosscuts this standoff with the final flashback that answers for Harmonica’s past.

Here, in a harrowing, yet gorgeously shot landscape, Frank is found to be the man responsible for killing Harmonica’s brother—this murder achieved by forcing Harmonica to balance his brother’s feet beneath a noose affixed to the town’s bell. To solidify this humiliation, Frank forces the eponymous harmonica into the character’s mouth—forcing the older brother to push himself off from his shoulder’s rather than endure this sordid murder and allow Frank the satisfaction. After drawing out this agonizing, yet spectacular climax to its breaking point, the shootout finally commences and ends just that next second later—with Harmonica finally returning the favor and harmonica into Frank’s own mouth.

Amidst this shootout, a dying Cheyenne has been dialoguing with Jill McBain in regards to the commencement of the railroad and of men like Harmonica and Frank—noting that those type of men: “have something inside…something to do with death.” And indeed, moments after this showdown with Frank, Harmonica arrives—ready to leave Sweetwater, and soon to be joined by Cheyenne. As the two ride out, Cheyenne’s clandestine bullet wound proves to be fatal—leaving Harmonica to hear this famed bandit of the frontier groaning in pain and begging to be left alone before he keels over to die amidst the dust and dirt.

While the Dollars Trilogy, and so many other Westerns of note, almost unanimously end on a note of triumph for these characters, this conclusion—again echoing in tone, style, and visuals to those films of the genre’s past—instead modulates these archetypes to elicit a more melancholic culmination toward the termination of these men of the West who have met their final fates—either to die with their face in the dirt or to flee alone onto the next town as a man with no name or place to call home. Despite the odious actions committed by Frank—the film opens with him gunning down an innocent child after massacring the boy’s family—this is not a triumphant shootout as seen in most Westerns. Instead, it’s the fulfillment of Harmonica’s revenge and the completion of a time when him and Cheyenne could lead their lives with trigger-quick fingers. Rather, this shootout signifies the end of these archetypes.

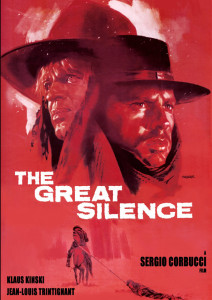

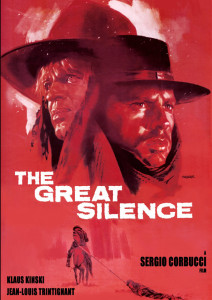

While Once Upon A Time in The West manages to simultaneously honor these ideals of the West while also considering the despair of these characters and the demise of their era to, in effect, create the “ultimate” Western, Sergio Corbucci—the second Sergio of the Spaghetti Westerns—also uses the time-honored traditions of the genre to create the paradigm of the “Anti-Western” as seen through The Great Silence.

Whereas Once Upon A Time in the West synthesized and amalgamated all those conventions of the genre and unified them under one umbrella of an epic Spaghetti Western film to elicit those themes discussed above, The Great Silence turns toward the opposite direction. Corbucci takes every conceivable staple of the genre and opts for its total antipodal opposite to arrive at a similar destination of consideration upon the end of the West.

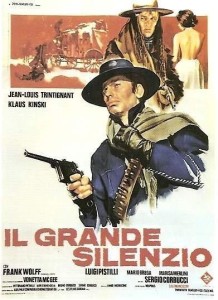

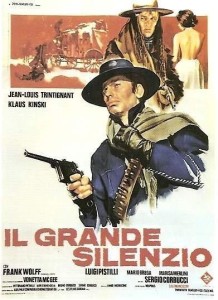

Released the same year of 1968, Corbucci’s The Great Silence takes place during a brutal, relentless winter within Snowhill, Utah 1898. These severe conditions have prompted the poor to rob: labeling them criminals in the process, and placing a bounty on their head as a result. Consequentially, the town has transformed into a haven for bounty hunters—mostly psychotic men who have coopted the job description as an outlet for their violent tendencies. The worst of which can be found in the film’s main villain—Loco (Klaus Kinski). However, hope arrives in the form of a mute gunslinger who has made it his mission to hunt down such bounty hunters—the eponymous Silence (Jean-Louis Trintignant).

Despite this deceptively simple set-up, The Great Silence revels in the gray morass of law upon the Western frontier; specifically, the idea of punishing the unlawful and of the tricky line of empowering those with the means of such punishment in the name of upholding justice and those criminals who justify their darker impulses in the name of upholding justice.

Moreover, the harsh conditions of this burgeoning civilization help stress this idea of man attempting to impose his sense of righteousness against the barbaric and untamable instincts of human nature. And while Leone looks to the traditions of the genre to highlight these ideas, Corbucci instead chooses to buck these traditions and favors the more unconventional approach. While the immediate instinct of almost every Western is to imagine a hot, arid desert across a dirty terrain populated by cacti across sere topography, Corbucci instead envisions an unbearably cold and desolate winter blizzard to saturate the atmosphere of his Western setting. While the unbearable heat of the desert certainly conjures ideas of man’s attempt to dominant a savage terrain, the frigid and bleak conditions of the unyielding winter snow serves a similar purpose of highlighting man’s insignificance in comparison to the scope of his surrounding nature.

Next, Corbucci subverts the archetype of the quiet gunslinger as found through the main character of Silence. While Leone’s men with no name—from Eastwood in the Dollars Trilogy to Harmonica in Once Upon A Time in the West—were all heroes of few words who expressed themselves more with a sharp stare than through any long speeches, Corbucci takes this character archetype to its very extreme: by literally making him a mute. While Leone’s heroes could be almost comically reticent to talk, Silence is not only literally a man made silent from having his vocal chords slashed as a boy, but in literally being incapable of making sounds—as seen when a bandit burns his hand, and he tries to scream but no sound can be produced.

In stark and ironic contrast, however, Corbucci pits this mute gunslinger against the loquacious lunatic named Loco played by Klaus Kinski. Within the severe conditions that have forced the poor to rob for food, and thereby placing a bounty on their head for the crime, Loco has adopted the bounty hunter profession as both a livelihood and ostensibly as a creative outlet for his psychotic tendencies. He has read into the “dead or alive” policy quite literally and often opts for the former. However, after hunting down the husband of a woman named Pauline, the widow calls upon the help of the legendary Silence—famous along the frontier for his penchant of avenging against bounty hunters. Still, Loco is well aware of Silence’s modus operandi. In order to justifiable kill these bounty hunters, Silence will taunt the men into drawing their guns then shoot them before witnesses—allowing him to legally claim self-defense in killing them.

While most Westerns use these ideas of bounty hunters and the burgeoning laws of civilization as an excuse for black-and-white tales of morality, a protagonist clearly on the side of the law fighting against those on its opposite, The Great Silence instead uses the juxtaposition of these two characters to highlight the very murky line that separates these two agencies of good and evil.

For in actuality, there is not much difference between these two men who both make a profession out of killing people. Both exploit the terminology of the law in order to fulfill those impulses of their personal ego. While Loco’s are geared toward greed and an excuse to execute those that bother him (namely blacks, as evidenced by his racist remarks after killing Pauline’s husband), Silence’s flashback demonstrates that his hatred for bounty hunters comes from the massacre of his family (and his vocal chords)—effectively demonstrating that Silence works more out of a quest for vengeance than one of objective justice.

Additionally, Silence’s methods of drawing bounty hunters into a fight and then exploiting execution via self-defense again highlights that Silence hardly deserves a more honorable status for finding methods of working around the law to fulfill his blood sake than Loco. Corbucci cements this similarity between the two men of the gun by having both characters request the same services for their fees of a thousand dollars (Loco for his bounty; Silence’s charge to Pauline for killing Loco). Again, while in almost all manner of Westerns, one can find bounty hunters, sheriffs, and bandits with a number on their head for their crimes—The Great Silence truly separates itself by making a spectacle out of questioning the very gray morality lying just beneath these thin veneers of laws proposed by this developing town of the West.

Another figure hoping to resolve these complicated moral and legal quandaries arrives in Sheriff Gideon Burnett (Frank Wolff). The Sheriff recognizes the false form of the legality currently being exploited by the town’s inhabitants, but with very little power in that these bounty killers are working within the codified boundaries of the law, the Sheriff finally appeals to the townsfolk and promises that if the bandits are just given food then they will be able to live in peace until amnesty arrives from the Governor—an amnesty that should effectively wipe out the cause of the bounty hunters. Nonetheless, after Loco becomes temporarily arrested, the two exchange an interesting dialogue in questioning the philosophy of the law:

Loco: You hate me because I kill bandits, but you do the same thing ‘cus you give ‘em to the hangman.

Sheriff: That’s different. The law has a right to kill.

Loco: Why?

Sheriff: Because when the law kills, it’s not murder: it’s punishment. The death of a bandit must serve as an example to other people who will not go on killing—

Loco: Killer—

Sheriff: Shut up!

Despite Loco’s attempts to bewilder the Sheriff through this logic of the law, the Sheriff maintains his resolve to bring peace between the bandits, the town, and ridding themselves of opportunistic bounty hunters. While transporting Loco to the larger jail, he promises the bandits that food will be made available to them in order to maintain a peace between both sides until the Governor declares Amnesty—a pact to which the bandits agree. During his trek across the snowy landscapes, however, Loco manages to outwit the Sheriff and leave him murdered—allowing for his return back to Snow Hill.

With the bandits believing that they are free from harm, Loco arrives with his fellow bounty hunters and holds them hostage at gunpoint within the local saloon to draw out Silence for a final showdown. This plan is proven to be a success: as Silence does indeed come out of hiding to confront Loco. What follow, however, turns out to be one of the most bleak and morbid endings in the history of the genre.

Upon arriving, Silence is unceremoniously shot down to die in the snow. When Paulina (now his lover) leaps to his side to comfort him in death, she is instantly killed, as well. Moments later, Loco and his gang then proceed to massacre the dozens of bandits in order to collect the bounties placed upon these poverty-stricken men, women, and children. As Loco leaves the saloon—alive and well and about to becoming much, much richer—the following text crawl materializes over the screen:

“The massacre of 1898, year of the Great Blizzard, finally brought forth fierce public condemnation of the bounty killers, who under the guise of false legality, made violent murder a profitable way of life. For many years, there was a clapboard sign at Snow Hill which carried this legend: ‘men’s boots can kick up the dust of this place for a thousand years, but nothing man can ever do will wipe out the blood stains of the poor folk who fell here.’”

While many Westerns certainly end on a note of deeply thematic, emotional catharsis or thought-provoking revelations concerning the era of the West, The Great Silence maintains the crown for the outright bleakest and most straightforward about its feelings toward these values. Although there is something to be said for how on-the-nose the film addresses these themes—especially vis-à-vis a text crawl—and especially in comparison to films that managed to weave these themes into the narrative without having to spell them out in such an explicit manner (Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, and as described at length above in Once Upon A Time In the West), The Great Silence still manages to elicit a truly devastating and memorable ending due to how profoundly unconventional Corbucci commits to his vision. Although the infamous “happy ending” was demanded (and is included on the DVD)—wherein Silence rises form the dead due to a bronze gauntlet (ripped straight from Fistful of Dollars) and the Sheriff incomprehensibly returns to support backup—one can easily see how hastily composed this scene was wrought—ensuring that Corbucci’s “unhappy” ending would endure.

And endured the film has.

Over time, the legacy of both The Great Silence and Corbucci has slowly grown to be recognized as the much more bizarre, brutal, and mean version of the Western when compared against his contemporary Sergio Leone. Moreover, the intriguing and compelling morality tale at the dark heart of The Great Silence offers insightful commentary into the contentious seeds of American morality that laid the foundation for the burgeoning twentieth century of civilization in the West—and one that marked the end of more simple morality tales of good versus evil.

Instead, as similarly explored in Once Upon A Time in the West, the two Sergios use the conventions of the Spaghetti Westerns and their archetypes to navigate the more treacherous roads that lay ahead for America in the imminent death of the Western. While Sergio Leone filtered his own artistic influences into an amalgamation of all those staples of the genre that called forth their grander traditions in order to complicate the character identities of the villain with the black hat, the impotence of the gun for the future, and the demise of this era in order to create the paradigm of the “ultimate” Western that speaks to so much of the genre’s tissue to compose a masterpiece of a film, Sergio Corbucci takes a starkly different approach.

Though achieving a similar goal through the complication of traditional moral norms—specifically in regards to the law—by embedding much more ambiguous character archetypes, and by utilizing the setting of a snowstorm to underscore the scope of these men attempting to conquer civilization in the face of unconquerable forces, Corbucci paints a much more unusual yet similarly thought-provoking thesis in consideration of the decline of these men and this era.

In both cases, these two masters of the Spaghetti Western genre imbued their own specific sensibilities into the best films of a genre unto which—not unlike the lone gunman protagonists of their narratives—arrived as outsiders but left as men who produced an immeasurable impression not only upon the genre at hand but filmmaking at large…who contributed immersive, groundbreaking films toward a subgenre largely cultivated into their own…and who questioned the essence of that very genre toward which they had ultimately constructed their careers. As a result, though Corbucci would go on to create other commendable cracks at the genre (Companeros in particular), and as much as a masterpiece as Leone’s The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly remains, there is something special about both of these films’ ability to render such a complicated and thought-provoking statement toward these themes of the genre as demonstrated by their remarkable narratives. A statement that speaks to issues of masculinity, human nature, genre conventions, and the future of America at large as seen through the genre of the Western.

As mentioned, the debut film sets itself squarely within the realm of the horror genre—only to magnify certain genre conventions to the extreme while also managing to establish some new ones. Having just arrived after the birth of the teen slasher, (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween, Friday the 13th), The Evil Dead isolates these college students in a remote cabin surrounded by woods, marshes, and a thick atmosphere of menace that seems to saturate every scene. More importantly, it is their exploration of the cabin’s subterranean cellar that the five find the taped recordings of the Naturom Demonto (Necronomicon Ex-Mortis in later films)—the Sumerian grimoire capable of unleashing supernatural entities that lie somewhere between the demonically possessed and a zombie—called Deadites.

As mentioned, the debut film sets itself squarely within the realm of the horror genre—only to magnify certain genre conventions to the extreme while also managing to establish some new ones. Having just arrived after the birth of the teen slasher, (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween, Friday the 13th), The Evil Dead isolates these college students in a remote cabin surrounded by woods, marshes, and a thick atmosphere of menace that seems to saturate every scene. More importantly, it is their exploration of the cabin’s subterranean cellar that the five find the taped recordings of the Naturom Demonto (Necronomicon Ex-Mortis in later films)—the Sumerian grimoire capable of unleashing supernatural entities that lie somewhere between the demonically possessed and a zombie—called Deadites.

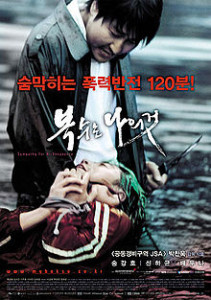

Finally, after electrocuting Yeong to death, and after Ryu’s discovery of her corpse, the two men began a tense standoff waiting to murder the other. Ultimately, Dong-jin proves the victor after rigging his home with an electrical trap that knocks Ryu unconscious. Now hauling Ryu back to the lake that proved to be the site of his daughter’s death, the father forces Ryu to undergo that same punishment that engendered his daughter’s death. Though Dong-jin acknowledges that Ryu may be a good man, the father also explains that he has been left with no recourse but to kill him due to balance out the tragedy of his daughter’s death. This leads to the brutal, stomach-turning climax, where Dong-jin hacks off both of Ryu’s Achilles Tendons to induce his drowning.

Finally, after electrocuting Yeong to death, and after Ryu’s discovery of her corpse, the two men began a tense standoff waiting to murder the other. Ultimately, Dong-jin proves the victor after rigging his home with an electrical trap that knocks Ryu unconscious. Now hauling Ryu back to the lake that proved to be the site of his daughter’s death, the father forces Ryu to undergo that same punishment that engendered his daughter’s death. Though Dong-jin acknowledges that Ryu may be a good man, the father also explains that he has been left with no recourse but to kill him due to balance out the tragedy of his daughter’s death. This leads to the brutal, stomach-turning climax, where Dong-jin hacks off both of Ryu’s Achilles Tendons to induce his drowning.