Not unlike Polanski’s unofficial Apartment Trilogy, Alan J. Pakula’s “Paranoia” Trilogy finds its three films united through a similar sense of mood and theme rather than a serialized story. Starting with 1971’s Klute, then The Parallax View in 1974, and concluding in 1976 with All The President’s Men, the trio of films weave a palpable atmosphere of unease—often through the prism of political underpinnings—while following a protagonist’s dangerous journey through an realm of suspense and intrigue. Although Klute situates itself firmly within the detective genre, the following films would inhabit specific arenas within the political thriller—escalating in scope each time—that address themes of grand conspiracy while suffocating the viewer in an atmosphere of dread.

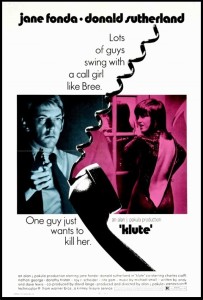

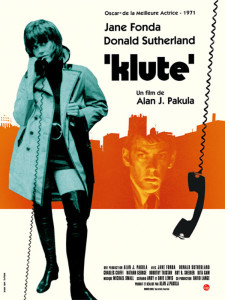

KLUTE

1971’s Klute marks the first film in this Paranoia Trilogy—starring Donald Sutherland as the eponymous P.I. and Jane Fonda as the prostitute at the crux of his case. Following the disappearance of executive Tom Gruneman, the police reveal a series of disturbing, explicit letters from him to a prostitute named Bree Daniels in New York. Though the police are unable to ascertain any other real clues, family friend Peter Cable hires Klute to investigate.

Upon his arrival in New York, Klute begins a complex relationship with Bree that toes the line between business and pleasure for both parties. However, Bree also presents a portrait of the prostitute with more depth than the archetype usually allows: a woman on the verge of wanting more, spending considerable time in poignant psychiatric sessions, charged by a variety of emotions, and with a distinctive personality brought to life from the marriage of the writing and Fonda’s indelible performance.

Nonetheless, as Klute’s able to ascertain some details regarding a john that violently attacked her in the past, the two become subject to a number of incidents that hint toward her being stalked—escalating the sense of paranoia already present in the narrative. When she and Klute also realize that the other prostitutes who committed “suicide” were actually murdered by the same man likely responsible for Gruneman’s disappearance, her life becomes further endangered unless Klute can stop the killer.

More than anything else, and despite the character of the title, the film offers an exceptional character study through the character of Fonda’s prostitute—Bree Daniels. Both Fonda’s performance and the writing compose a character so unlike most prostitutes in film—neither the manic pixy dream girl with a heart of gold, nor a tragic nymphomaniac, nor any of the other typical prostitute portrayals in fiction—but instead, a depiction of a very rounded woman full of flaws, humor, and recognizable humanity.

From her opening manipulation of a customer, to her manipulating Klute, to her own admission of a needing control, Bree Daniels encapsulates an all-too-rare example of a female character with specific depth and writing that respects a character found on such fringes of society by detailing her life with these distinctive personality details. The constant conflict between her need for control, and her inability to control the danger around her, also adds a layer of complexity that allows for this compelling characterization to drive much of the surface level plot. Her use of sex as a means of control might remind viewers of the femme fatales from film noir’s past, but her deep insecurities and visible humanity illuminated through Fonda’s performance elevate this character into a unique persona that defies normal genre function.

In contrast, Sutherland’s Klute typifies the brooding figure of detective mystery, yet his complex relationship with Bree—the continual resistance mixed with magnetized attraction—causes considerable intrigue to be added aside from the central mystery of the case. Sutherland’s face and stern eyes are able to imbue a specific feeling far more than most actors are capable through long dialogue exchanges, and his commendable restraint in ever breaking character in favor of a flashier performance deserves special praise.

Moreover, Pakula continually frames the two characters as just out danger’s reach in order to heighten the atmospheric feeling of claustrophobia within the sprawling New York setting. Point-of-view shots of Bree from the killer’s perspective constantly remind the audience that this woman able to deftly manipulate so many men remains firmly under the watch of this dangerous figure from her past.

Additionally, Pakula uses sound to maximum effect in order to continually disorient the audience’s sense of comfort. With taped recordings of Bree’s promiscuous phone calls, to the sound of footsteps on a roof, to the quiet corridors of a factory, this unnerving feeling of imminent danger always feels just at the edge of each scene—no scene more indicative and haunting of this power than that of the climax.

After Cable has been revealed as the betrayer to Gruneman and the killer of the other call girls, he finally manages to trap Bree at a garment factory. There, the menacing figure begins to taunt her—finally forcing her to listen to an audio recording of his killing a fellow call girl—in an unforgettably disturbing scene constructed through the use of a recording and Fonda’s face of horror. The recording of this man murdering a woman and her pitiful shriek as life escapes demands for the audience to imagine this gruesome scenario within their own imagination, and through this device, creates an atmosphere of horror that other films often aspire toward but through lesser means (e.g. cheap special effects/shock gore). Fonda’s silent, captivating performance in this climactic moment—as a woman paralyzed by her captor and now being psychologically tortured to the point of uncontrolled tears—only serves as further evidence for her well-deserved Oscar win.

Klute remains my favorite film in Pakula’s filmography, and a remarkable crime thriller that conjures a feeling of paranoia only paralleled by those films found in the very different genre of Polanski’s horror. Both performances stand out as career highlights for both actors, and the nuanced writing allows these distinctive characters to lend considerable depth to an already intriguing plot by examining this strange relationship between two figures on either side of the law.

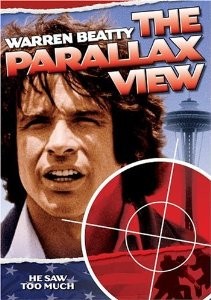

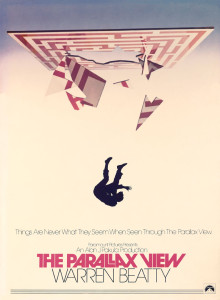

THE PARALLAX VIEW

Pakula’s follow up to this first film in his unofficial trilogy can be found in 1974’s The Parallax View. Here, Warren Beatty stars as dogged reporter Joe Frady—one of several witnesses to a shocking opening scene of a senator’s assassination atop the structure of Seattle’s Space Needle. Cutting to three years, several witnesses—including his ex-girlfriend—are being murdered in “accidental deaths” that demand his investigation into some wider conspiracy linking the murders.

This investigation leads to his uncovering of a mysterious group known as The Parallax Corporation. Going rogue and off-grid, Frady poses as a potential employee for The Parallax Corporation—only to learn that the Corporation employs anti-social personalities and others that do not conform to society in order to enact their political agendas through assassinations or terrorist attacks.

In comparing The Parallax View directly against its predecessor, certain structural parallels emerge that are worthy of consideration. In both cases, the main protagonist works as a detective—Klute explicitly as a P.I., but Frady also acting as an investigator vis-à-vis his job as a reporter—and then embroiling themselves in a case which they are pledged to solve before slowly transforming into a figure forced to face aspects of their identity previously considered resolute.

Though Klute’s transformation occurs on a much more introspective level, The Parallax View weaves Frady’s journey into the actual plot itself—and therefore, the viewer’s journey. Frady’s initial skepticism of any connection between these “accidental” murders, which he continually attempts to rationalize, finally dissolves when a Sheriff attempts to murder him in the sleepy town of Salmontail. His further induction into this secret society confirms his suspicions and incites his urgency in exposing this corrupt corporation operating behind the scenes of these political attacks reshaping the country.

These scenes of Frady’s covert investigations into the Parallax Corporation work as the best scenes in the film—ensuring that the audience remains in arrested suspense and drowned in dramatic irony. Specifically, his first training sequence, wherein Frady—and the audience—are subjected to a montage of historical photos juxtaposed against various words of ideals like “ me”, “country”, and “love” stands as the most memorable and thought-provoking scene in the film. This montage works like a piece of experimental art suddenly spliced into the middle of the film—instantly recapturing the audience’s attention and delivering an exhilarating sequence that returns the audience to a mood of vulnerability and surprise.

As the plot plods forward and Frady’s involvement with this mysterious corporation escalates into one with serious consequences for both his life and the country, the paranoia of the trilogy’s title kicks into high gear and allows for a gripping climax and ambiguous finale that challenges the audience in a way that the best films of this era were capable. Gordon Willis’ cinematography in this climactic scene deserves special attention. As Frady attempts to stop another assassination, he hides in the darkened rafters above the ground floor of the spacious convention floor, and the suspenseful editing between the shadows of the rafters above and this brightly illumined setting below works to spellbinding effect.

Still, The Parallax View stands as the weakest of the three. Unlike the other two films, The Parallax View contains certain sequence of fat that dilute the streamlined narrative. The first example of this occurs in Frady’s fist-fight brawl with the Deputy in the town of Salmontail that would not be out of place in a fifties Western. The fight goes on for an almost comical amount of time, and though the Sheriff has some humorous remarks in the aftermath, it’s an example of noticeable fat on the running-time that is absent from either of the other films. Another example of this occurs in the form of an oddly placed car-chase between Frady and the police that feels like it belongs in a different genre altogether. There are other smaller instances of this type of padding in this film, and these small criticisms add up in a way that causes this film to slag—remarkable and commendable as it is in other areas of craft—to feel like the lesser of the three in terms of storytelling and tone.

Despite these criticisms, the film still deserves its ranking as one of the most intriguing of the seventies. It stands as another laudable entry in this distinct genre of the paranoid thriller pioneered by Pakula, but when laid in direct comparison to the other two films, these glaring shortcomings described above stand in sharp contrast to the streamlined focus and authority of atmosphere found more successfully in the former and the latter.

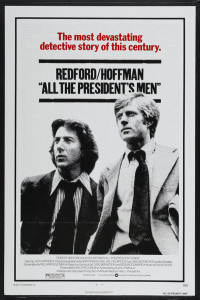

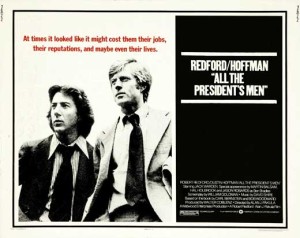

ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN

Pakula’s conclusion to this unofficial trilogy in 1976 resulted in arguably his most critically acclaimed film to date as a director—All The President’s Men. An adaptation of the book written years after by the movie’s two main character’s, the film follows young Washington post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, as they relentless pursue answers to the break-in at Watergate Hotel—only to uncover the notorious scandal that would culminate in the resignation of President Richard Nixon.

A plot summary seems unnecessary for this third entry, as it almost exclusively concerns the laser-focused investigation of Woodward and Bernstein in the aftermath of the perplexing Watergate break-in. Not unlike Frady, the two again take on the role of detectives (with the poster’s tagline claiming: “The most devastating detective story of this century”) in order to collect evidence and information on this grand conspiracy with profound consequences for the narrative of America and a climax that places both their lives and the concept of American authorities at stake.

The film neatly summarizes and manages to make compelling the enormously complicated pieces at play—from the testimony of secretaries, to the infamous Deep Throat, to various committee members all with unmemorable names—the script somehow always makes sure that the flow of information never becomes too overwhelming or lost in the shuffle of the rapid-paced storytelling. As the two reporters are constantly put in the difficult position of prying information from reticent, guilty members who often want to do the right thing but are also aware of the enormous ramifications in doing so, these exchanges never falter in finding ways to imbue a sense of simultaneous triumph and defeat.

Each source, clue, or admission found by the reporters always allows for the reporters to keep their heads above water in the face of immense opposition —from colleagues, from the public, to the White House itself—and every little victory helps in reminding just what underdogs these two reporters were when tasked with writing such an impossible story.

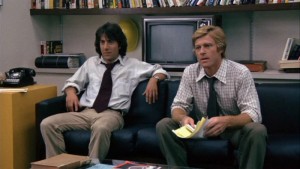

Redford and Hoffman’s performance help convey this range of emotions—from desperation, to stolid determinism, to unenviable publicity, to momentary defeat to absolute triumph—but always in relation to the fluctuations of the case. Because of this laser-focus in hoping to move the story forward without drowning in exposition, the character themselves are only given the briefest personality details (e.g. Bernstein’s chain-smoking) but again, the performances help lend a depth to the emotions and humanizing of both men beyond that of functionary characters by demonstrating their desperation, frustration, and sense of camaraderie in every scene which they share.

Hal Holbrook’s performance as the infamous Deep Throat source serves as an almost literal manifestation of the paranoid feelings so perceptible in Pakula’s vision: a mysterious figure cloaked in shadow, who speaks in riddles, and charges each scene with a captivating sense of ominous power. These scenes between Deep Throat and Woodward are captured once again by familiar Pakula collaborator and “Prince of Darkness” Gordon Willis to astounding effect—always finding a perfect composition between shadow, darkness, and cigarette glow to cast Holbrook as some kind of sinister wraith at the center of this nightmarish scandal.

Famed screenwriter William Goldman deserves similar credit for synthesizing so many disparate elements and never losing the thread of what is at stake for every character entangled in this web—not just Woodward and Bernstein, but those lost in the mix of Nixon’s committee, secretaries fearful of their lives, and the employees of The Washington Post concerned about the reputation of their own careers. Moreover, his sense of pacing perfectly complement the atmospheric paranoia of Pakula’s interest—and the latter third helps raise the sense of paranoia to noticeable effect once Deep Throat confesses to Woodward that their lives are now at stake. From clicking phones, to having to communicate over written messages, to anonymous men that seem to be following them, Goldman incorporates a range of devices to expand this nightmarish feeling to new heights in comparison to the former films.

At last, the final scene—a juxtaposition of Nixon’s televised Presidential oath against dissolves of the reporters typing the story that would cause his resignation—works to tremendous, subtle effect and serves as a perfect visual image for the film’s thesis on display: two reporters who used the power of the press to bring down the most powerful man in the country.

Like the other two films, All The President’s Men revels in an atmosphere of tension and palpable sense of paranoia that find its strength in the taut storytelling on display and through characters determined to find answers within a cryptic maze of suspicion. Starting with Klute, then expanded in The Parallax View, and culminating in All The President’s Men, Pakula’s strong command of tone always keeps the audience in a state of suspense and unease—positioning their point-of-view directly in line with the protagonist attempting to navigate this unfamiliar realm of darkness to find some sense of truth, and then only for those answers to challenge the core ideals. In all aspects of his Paranoia Trilogy, Pakula provides more thought-provoking questions than he does answers—challenging the viewer to examine their own ideas of identity, country, and authority at large.

Pingback: Film Appreciation: All The President’s Men