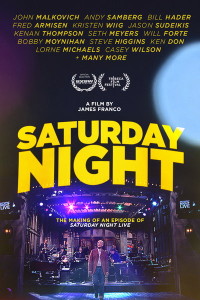

“So I’ve got this idea…” interjects a writer in the Monday morning pitch session to Lorne Michaels from a scene in Saturday Night, the James Franco directed-documentary that details the anxious, frenetic, and arduous process of the week leading up to the final live airing of an episode of Saturday Night Live. While the nearly two-hour long documentary indulges in all the behind-the-scenes pleasures sure to satisfy die-hard SNL fans hoping for a glimpse into exactly how the iconic show operates on a day-to-day basis, the dynamics between the cast, and the integration of the host into the show, Saturday Night also examines a creative process between the cast and crew that has allowed the show to evolve into perhaps the premiere comedy institution throughout the decades.

With John Malkovich hosting the episode in question, the documentary opens behind the host’s back and follows his entrance to the main stage. For any dedicated viewer, it’s an disorienting but compelling experience that simulates the host’s point-of-view, especially as the exclamatory “Live form New York, it’s Saturday Night!” is heard as a distant echo through the walls. The structure then jumps back to the previous Monday and follows the agonizing, adrenaline-fueled writing days shared between the cast and writers as they prepare for the Wednesday table read. Some of the writers appear almost overwhelmed by panic, others energized by it, some of the veterans almost annoyed by it, but it becomes quickly clear that the camaraderie of the experience is as fundamental to the cast’s chemistry as the material over which they are funneling their energies within this difficult timeframe.

Immediately, an evident sense of fraternity becomes apparent amongst the writers. At somewhere between three and four in the morning, Mulaney, Hader, and Jorma Taccone are still stationed before their laptops with a beautiful New York skyline limned by a descending moon in the office window behind them. And yet, the three are exchanging ideas, laughs, and impressions as rapid-fire and enthusiastic as a bunch of twelve-year-olds cracking up in a tree house. Other writers almost seem ready to collapse with exhaustion; others (in a scene with Kristen Wiig) are vigorously attempting to calculate whether the farting sound produced by an electronic keyboard “outstays its welcome”.

Next, after intermittent naps between dawn and lunch, the writers send in their preliminary sketch scripts to the producers, who then sort through nearly fifty sketch ideas for the Wednesday table read. Here, the writers present the material to the host and producers for initial review. The performers sit around a large conference table and act out the sketches—some on the last legs of their caffeinated fumes from the night before.

And yet, as soon as they begin reading the scripts, the cast comes to life as effortless as ever. Bill Hader, Fred Armisen, Kristen Wiig, Sudekeis, and the like imbuing their idiosyncratic characters with such an astounding level of natural perfection that they risk intimidating those who have recently joined the ranks or need more time to fully prepare. After one sketch between Samberg and Malkovich absolutely electrifies the room, poor Casey Wilson’s not completely yet realized impression of a Liza Minnelli sketch leaves the room bored or cringing. It’s a brutal scene, but yet another fascinating glimpse into how mercifully the cast of this show must be constantly ready to produce the best they have to offer without any chance for artificial acting. More than anything else, a spirit of inevitable competition also becomes discernible amongst those involved. Will Arnett analogizes something similar to cheerleading try-outs, and the metaphor doesn’t seem far off.

After the Wednesday table read, a printed sheet informs the cast whose sketches have been made the cut, in what again feels very analogous to high school students hoping to be selected for the lead role of the school play. And yet, there is no time for heartbreak or regret, as the cast is already quickly on their way to blocking out scenes or rapidly editing each sketch to milk out every single second for the maximum amount of laughter.

In between this round-the-clock rehearsal and preparations for the show, James Franco—serving as director—interrupts with interviews from producers and certain cast members. The most interesting are undoubtedly from producer Steve Higgins and creator/exec producer Lorne Michaels, who shed light on their realizations about the demands of the job from a creative standpoint, as well as how they’re able to cope when the show fails worse than they had expected, to which both more or less reply that next week show’s is already just a few days away.

By actual Saturday, there’s a palpable sense of tension to ensure that there are no small mistakes that may lead to catastrophe. Costumes, set-dressing, final sketch cuts, and constant fine combing over certain dialogue soon consumes every minute of the cast and crew’s lives. In one of Bill Hader’s funniest sketches, he and Fred Armisen are figuring out the best version of screaming out their incoherent Italian dialogue down to the last minute, determining when exactly would be the funniest time to be interrupting one another’s nonsensical Italian language. It’s an incredibly impressive demonstration of how meticulous these performers, even the most naturally gifted, remain under joyful duress to ensure that their output exemplifies the absolute best of their capabilities, for as Lorne Michaels reiterates to Franco: “You’re only as good as your last show”.

And by the actual live airing, we’ve returned to Malkovich’s disorienting entrance to the main stage. At this point, the charge of the audience and knowledge of the live broadcast seems to have revitalized the cast and crew back to their manic Monday enthusiasm. The show carries on successfully, and seemingly without a hitch (despite Hader’s complaint backstage that he and Armisen missed a cue [which no one else, including a head writer, seems to have noticed]). More interestingly, there are other interesting behind-the-scene glimpses like a woman specifically designated to make sure that the host’s path is cleared in between set-ups, as they are frantically whisked from sketch to sketch.

After the show, the doc cuts to black before a final return to the next Monday morning, where Lorne Michaels introduces the next host, before another writer pipes in with the familiar “So I’ve go this idea” line. The cycle continues, and another week of sleepless nights, fruitless perfectionism, and the childlike joy of performing for the laughter of millions begins anew. While Saturday Night is certainly worth seeking out for even the most casual SNL fan as an intimate backstage glance into the machinations that allow for a new show every week, the doc also offers a thought-provoking introspection into how the creative process of these performers has distilled itself into a very unique style of performance art through the decades.

The cast and crew must negotiate between impossible deadlines, a constant demand for innovative, yet broad comedy, and still deliver a quality show that demonstrates professional production values and the natural ease of its gifted performers. By the arrival of the next Monday morning, the doc illustrates how fluid the creative process must remain, and that no matter how successful or abysmal the previous production may have ultimately proved, that the show must go on, and that they truly are only as good as their last show. Nonetheless, if the long and popular history of SNL has proven anything, it’s that their last show—no matter whether it was filled with constant laughter or an assortment of misfires—is populated by skilled creators who are determined to perform with everything they have to offer…live on television…every Saturday night.

Pingback: Saturday Night Review: The SNL Documentary directed by James Franco – Movie Categories.com