As a very dark descendent to shows like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, the arrival of Black Mirror—an hour-long television series anthology hailing from Britain—delivers three of the most compelling and disturbing episodes to address similar issues of human nature through the prism of the sci-fi genre. While other shows have admirably attempted to replicate the memorable twists and horrors of the most famous Rod Serling episodes, Black Mirror distinguishes itself from such imitators by creating incredibly thought-provoking scenarios that demand the viewer engage with morally ambiguous questions, where no resolution lies without serious consequences, and exceptional writing that further separates the material from its sci-fi siblings.

The first episode “The National Anthem” announces very loudly exactly how this show will differentiate itself from its predecessors (and most of the current television landscape) with a premise that involves the Prime Minister receiving a call from terrorists demanding that in order for the princess to be released, he need answer only one demand…

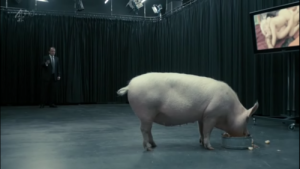

A demand that involves him and a pig—intimately—on live television.

While most shows would immediately crumble upon such an ostensibly crude premise, by either winking at the audience or failing to adequately construct a wall of realistic approach around such an absurdity, this is where Black Mirror delivers in spades. As the series successfully steers in exactly the opposite direction: by maintaining a tone as deadly serious as possible. Every conceivable question, short-cut, or excuse as to how the Prime Minister may wiggle his way out of the horrific situation is addressed and then dismantled—and not through plodding, expository scenes—but rapid-fire dialogue amidst the myriad sociological levels detailed in the story: newsrooms, the government, the bars of everyday citizens…

As a result, the episode intensifies with an unyielding sense of urgency and anxiety. Where so many shows would narratively deflate, or undermine such attempts maintaining a serious tone, Black Mirror refuses to let the viewer off the hook until the end of the hour run-time. And even then, the episode is not finished. In true Twilight Zone fashion, the consequences of the Prime Minister’s choice deliver an ambiguous resolution: one that appears to have succeeded on the surface but has irreparably damaged his interior psychology—and most especially, his wife’s. While some have argued that this episode is not indicative of the show’s overall agenda, this episode actually better exemplifies the extreme nature of the plotting created by the writers and remains an episode that—for better or worse—evokes discussion and cannot be forgotten. Moreover, “The National Anthem” addresses our modern attitudes toward certain omnipresent technology (specifically social media/texting) through a very extreme, though altogether believable, depiction of current technological consequences.

“Fifteen Million Merits”—episode two of the trio—establishes a more allegorical, futuristic setting than any of the other episodes to discuss a multitude of similar modern-day issues: fame, social media, human connection, and how modern technology has disrupted the most human elements in each. The episode opens with Bing (Daniel Kaluuya) awakening within a small, prison-like cell of four walls that are also video monitors. Day-to-day life in this futuristic setting is presented in similar, suffocating technological parameters: every single decision is made by tapping a wall-sized monitor, exercising on a bike before another monitor which earns one “merits” to purchase whatever they made need, and constant sexual advertisements that intrude through these omnipresent monitors from which citizens cannot escape without being penalized (even placing your hands over your eyes causes the video to freeze until the eyes are freed).

Although the weakest of the three episodes, the production values are incredible. Every single detail of this world of literally inescapable electronics is specifically realized and believably presented. While the writing remains much, much, much smarter than most television would ever have the ambitions to approach, it also addresses its themes and larger ideals more on-the-nose and less subtly than the others (with Bing’s histrionic speech yelling/spelling out these themes above in an apoplectic monologue serving as perhaps the most indicative example).

Moreover, the episode discusses such a multitude of issues: from skewering the hollowness of fame, of the virtual competition of social media, of society’s shaming the obsese, of the unavoidable presence of contemporary technology, of the loss of human connection from technology—not to mention the various echoes of 1984, Fahrenheit 451, and similar bleak, dystopian settings—that the more successful aspects of the episode are marred by these less successful executions. Nonetheless, the episode still delivers some very thought-provoking ideas and remains compelling in its continual unfolding of consequences and futuristic setting that undeniably mirrors our modern-day era.

Finally, the last episode—“The Entire History of You”—offers the best episode of the season and similarly works as a stand-alone scenario that presents a very disturbing portrait of delving into specific scientific advancements. The episode revolves around a future where a technological device allows users to record and replay their memories; and more specifically, the premise revolves a husband who begins to suspect his wife is having an affair after replaying his memories of a dinner party over and over.

The episode succeeds so well in its execution by conjuring a futuristic setting that is not altogether too removed from our own—despite the existence of such a revolutionary technology. Additionally, the plot is not weighed down by tedious explanation and constant overanalyzing over how such a device would filter into the lives of ordinary citizens; but instead, the story plunges into a premise that would not be out of place in a contemporary soap drama centered on themes of mistrust in marriage, while the technology merrily serves as the catalyst of the plot.

Furthermore, as seen in the best of hard sci-fi, “The Entire History of You” uses the feasibility of the technology to illume profound issues of human nature. The episode delves into issues of trust, memory, and time, through a very well-plotted and deceitfully simple premise of a man who believes his wife might be in love with another man. Like the other episodes, the writing allows for a constant escalation of stakes and sense of urgency that—accompanied with the incredible acting between Toby Kebbel and Jodie Whittaker—generates a compelling vision of the ramifications produced by such a technological consequence. And also like the other two, the episode concludes on a very ambiguous note—one that satisfies the reality of such a scenario but also devastates the viewer with the emotional aftermath of abiding by such authentic storytelling—and should be applauded for doing so.

In all three episodes, Black Mirror develops a haunting and thought-provoking tapestry of the consequences that arise from our current forays into technology and ambitions beyond the horizon. As a result, the series stands up to its namesake—reflecting a genuine, creative depiction of how such viable futures may be realized by both the best and worst qualities of human nature. Similarly, such an anthology format allows for numerous issues to be explored: from fame, to an overwhelming technological presence, to the loss of human values in the face of each, and the redistribution of humanity’s connection spurred by such oversight. As a result, the first season concludes as an unforgettable collection of original sci-fi: one that shatters former boundaries found in the television medium and ascends to rank alongside one of the best offerings in the genre.